Boxes sit stacked in a compact room on the second story of the Afro-American newspaper’s Baltimore headquarters, just down the street from the Johns Hopkins Homewood campus. They’re standard document boxes, brown, rectangular, with removable lids. They rest on metal shelving units, nearly floor to ceiling, that line and divide the room. Every box looks the same, though each has its own unique number written on it. They consume the room. Boxes, boxes, everywhere.

“This room down here contains 359 boxes,” says John Gartrell, the Afro-American archivist, as he conducts a tour of the archive. “The four rooms I showed you plus the hall cabinet plus the morgue—those are part of our general files. So, as you can see, it’s a lot.” As understatements go, that’s up there with “Houston, we’ve had a problem.”

The Afro-American is one of the oldest, family-owned, continuously publishing newspapers in the country. It was founded in 1892 by John H. Murphy Sr., a former slave who earned his freedom by serving in the United States Colored Infantry’s 30th Regiment during the Civil War. It went on to publish as many as 13 editions nationwide, including one in Washington, D.C. Beginning in 1923, newspaper staff kept all the information used to create the paper’s content. These items were placed in envelopes that in turn were placed in boxes. The boxes sat in the Afro’s long-standing downtown Baltimore home. At some point, some of them were shipped to Bowie State University, where they sat on shelves. When the Afro relocated to its current location on North Charles Street in 1992, the archive’s entire box collection came with it.

Today, the Afro’s archive occupies its own seven-room expanse in the rear of the building. That area includes what’s called “the morgue”—stacks of bound copies of the original broadsheets dating from 1909 to the 1970s. A row of file cabinets maintains an additional archive of photographs, arranged in alphabetical order by proper name or subject matter. And then there are the boxes, taking over four of the archive’s seven rooms, each box containing metal-clasp envelopes that bear terse, handwritten descriptions of their contents. Those envelopes hold a smorgasbord of 20th-century historical ephemera: newspaper clippings; personal, professional, and internal newspaper correspondence; photographs; metal engraving plates from the era of movable type presses; school surveys and reports; funeral programs; pamphlets; government reports; business documents; editorial cartoons; and more. The archive’s four rooms of boxes contain approximately 154,600 envelopes and about 1,125 linear feet of documentation—roughly four football fields in length.

The full extent of just what the Afro’s archive contains has only recently been determined. In 2007, the Afro-American Newspapers Archives and Research Center partnered with Johns Hopkins University’s Sheridan Libraries Center for Educational Resources, plus the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences’ Center for Africana Studies, to create the Diaspora Pathways Archival Access Project (DPAAP), a program funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation that hired undergraduate and graduate students to write descriptions of the archive’s holdings, which were organized into a publicly accessible database. During the three years (2007–2010) of activity funded by the grant, 12 students from seven different institutions received an intense educational experience—not just a behind-the-scenes peek into a century of a newspaper’s existence but a firsthand understanding of how history gets written.

Mr. Joseph Gans, better known as “Joe” Gans, is a colored man and a pugilist. Mr. Gans gets more space in the white papers than all the respectable colored people in the state. Moral—if you wish to be noted in white folks’ paper become a fighter or a criminal. (Afro American Ledger [national edition], January 4, 1902)

HISTORY’S RAW MATERIALS, like fossils, are embedded in layers of time. Consider a drawer in your office desk or a hall bureau at home: Its jumbled contents form a visual collage of your recent past. History gets written when somebody sifts through the remains and ponders how all the pieces fit together.

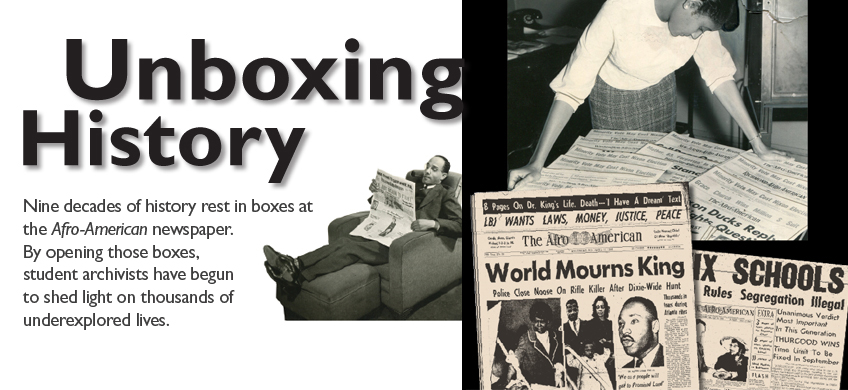

At one time, the Afro-American published 13 editions nationwide, including papers in Baltimore and Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy of the Afro-American Archive

Moira Hinderer knows how tedious that excavation can be. As DPAAP’s project manager, she has spent the last four years working with student interns doing the grunt work. Starting in January 2008, she would head over to the Afro’s second-floor archive and grab a numbered box off a shelf. She’d find a small desk in one of the archive’s overstuffed rooms, sit down, and open the box. She’d take one of the envelopes and enter its handwritten description into a database. She’d open the envelope to see what was inside, then make an inventory of its contents and enter that into the database. She’d return the items to the envelope, close it, and put it aside. Then she’d reach for another one and repeat the process—again, again, and again. When all the envelopes in a box were cataloged, she’d return the box to the exact spot from which she had gotten it. And then she’d grab another box and start the process again.

“Working in the archives has these incredible highs and lows because sometimes you see stuff that is just so cool and you run around and you show everybody else—‘Look at what I found!’” she says. “But that can be 15 minutes out of eight hours when you’re doing the most boring data entry stuff.”

Hinderer, who wears the sturdy eyeglasses of somebody who spends a great deal of time sorting information, is one of those multitasking academics who offer a mix of pragmatic expertise and academic specialty. She earned her PhD in history from the University of Chicago, and her dissertation, “Making African American Childhood: Chicago, 1915–1945,” explored everyday cultural life in the black community. She came to Johns Hopkins in 2007 as a postdoctoral fellow to manage the DPAAP. She has a joint appointment in the Department of History, where she lectures on 20th-century African-American history in the Center for Africana Studies.

Working on both the archival side and the educational/interpretive side of academic history gives Hinderer particular insight to the Afro’s holdings. They tell a different version of African-American history than what is popularly understood and presented, she says. Wikipedia, that great middlebrow reservoir of popular consensus, divides African-American history into 14 phases: African origins, slavery, revolutionary/early America, the antebellum period, the Civil War, emancipation and Reconstruction, Jim Crow, civil rights, the Great Migration and the Harlem Renaissance, World War I, World War II, the Second Great Migration, the [modern] civil rights movement, and the post–civil rights era. It’s a version that chronicles African-American history as an account of pure struggle and calamity.

The idea that contemporary African-American history is still an evolving narrative, however, is one of the more compelling arguments made by the Afro’s archive. The archived material provides a window into underexplored lives. Hinderer says that as a teacher of 20th-century black history, she sees the value of that alternate storyline. “I have students who come into my class, and their reference point for black history starts with the world they see around them. That’s Baltimore, unemployment, economic divestment, struggle, poverty. So black history is a story of suffering, and urban.

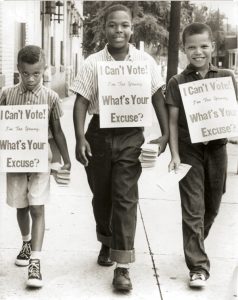

“For me, part of the problem is not to deny that but to complicate it,” she continues, and mentions the paper’s photography archive as an example. In the Afro, readers saw photos of strong African-American civic organizations and neighborhoods that weren’t being represented in other media outlets. “If you look at this visual record of this really intensive [African-American] community, then you can understand, yes, there’s this history of oppression. But even under the pressure of segregation, people are living these rich, full lives.”

Such materials are a treasure trove to cultural historians who previously might not have had access to such a wide range of information from African-American life. “It’s almost like the holy grail of African-American history,” says Marilyn Benaderet, who became one of the Afro’s first full-time archivists in 2006; she left the paper in 2009 to become the preservation services director for Preservation Maryland, the organization dedicated to protecting the state’s historical buildings, neighborhoods, landscapes, and archaeological sites. “This collection gives you insight into what the everyday person was doing,” she continues, citing examples of Afro coverage that show African-Americans going to work and to church. That sounds mundane, but that’s exactly what makes such images potent: that’s not how African-Americans were being represented in dominant media at the time. “We were living under slavery and then you skip straight to Martin Luther King and we’re all marching and rioting,” Benaderet says of photos of African-Americans that appeared in mainstream publications. “But what else were we doing?”

Benaderet was the Afro archivist when the DPAAP started and is familiar with its holdings. She curated historical exhibitions using materials culled from the holdings and assisted veteran Baltimore Sun columnist C. Fraser Smith in research for his book Here Lies Jim Crow: Civil Rights in Maryland, published by Johns Hopkins University Press in 2008. “I was so encouraged when Hopkins decided to become a participant in the [DPAAP] project because it opened [the collection] up to a larger community, specifically the academic community,” she says. “I think as African-American resources become more available, you’ll have more people who will be more willing to do research in the field. Years ago you may have had a topic in mind that you wanted to research as an African-American researcher, and the volume of information you could find would not even be enough to complete a project. Resources like this are going to eliminate situations like that.”

Black people make up more than 11 percent of the nation’s population, and there is no reason why colleges should not offer courses and degrees in black history, African history and culture, and the literature, sociology, and economics of the black man in America. Degrees are granted in Far Eastern studies, Russian studies, even hotel administration. Why not, then, a degree program dealing with this major aspect of American life? (Washington Afro-American, February 4, 1969)

DPAAP INTERN MARK Mehlinger, A&S ’10, discovered firsthand how frustrating archival research can be. Now a freelance photographer and an Afro Web editor, in 2006 and 2007 he was a Johns Hopkins undergraduate international studies and East Asian studies major taking a pair of classes with Ben Vinson III, the Krieger School vice dean for centers and interdepartmental and graduate programs and DPAAP’s co-principal investigator. (Candice Dalrymple, associate dean of university libraries and director of the Center for Educational Resources, is the grant’s other co-PI.) In the fall, Mehlinger took a seminar called Discourses in the African Diaspora; the following spring he followed that with a research practicum that worked through issues raised in the seminar—specifically, how immigration could affect a city. He spent hours in the Milton S. Eisenhower Library and Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library, combing through back issues of the Afro on microfilm.

These boys were part of a voter registration drive in Richmond, Virginia. Photo courtesy of the Afro-American Archive

“It wasn’t easy,” Mehlinger says, laughing as he recounts how he’d first do an online keyword search that pointed him toward a specific edition of the newspaper, then slowly page through the microfilm of that edition to determine if anything there addressed his research topic. “When you’re looking for such a specific thing, you’re not going to find those [key]words exactly when you’re searching through microfilm. I was able to find this and that, but there really wasn’t a lot.” So when he became a DPAAP intern in January 2008 and began cataloging the contents of Afro envelopes, he understood the value that specificity would hold for future researchers. He’d go through envelopes and come across an individual’s name in one box; in another box, he’d find an envelope labeled with a black fraternity’s letters and notice the same individual was the most socially prominent member of the organization. “So you realized these two things need to be associated,” he says.

Recognizing, noting, and digitally archiving these horizontal relationships is what lends the DPAAP database its power. Historical data—an event, a person, a place—has historical value and tells a story through its relationship to people, places, and events taking place around it. A historical fact becomes better understood through descriptive information surrounding that fact—an idea amplified when looking at journalism, history’s ostensible first draft. A newspaper’s morgue becomes a kind of collective memory, but one that was determined by the point of view of the institution that published it. As a black press, the Afro-American told different stories than the mainstream media of the time. The Afro “ran hard news,” says Asantewa Boakyewa, a DPAAP intern and now an administrator in the Center for Africana Studies. “But the editorial voice was very strong that this was supposed to be the voice of black Baltimore.” And through a black press’s different historical record, the archive opens up different histories for exploration. In the Afro, “blacks got married, blacks got PhDs, black people went to the theater, they were doctors,” Boakyewa says. “There was a whole culture, a whole way of life that was ignored by American society. It didn’t exist but in the black press.”

Mary Banks, A&S ’07, another DPAAP intern who participated as a graduate student in creative writing and publishing arts at the University of Baltimore, was interested to study news reports during segregation. “It’s one thing to read about it in the history books, and it’s another thing to actually see the articles of that time period and hear testimonials,” she says. “The people became real to me. When I read a textbook it can seem very far away and detached—that was a very long time ago. But when you start seeing the articles, it gives you a chance to have the people come to life as real people and real stories, and these were the adversities that they had to overcome.”

Marcus Allen, an undergraduate DPAAP intern from Morgan State University (where he is now a graduate student), remembers coming across a news story about a young girl who was being bullied in pre–World War II New York. She went home, got a gun, and shot the girl who had been bullying her. For Allen, that story and others he came across contradicted the popular assumption that families used to be stronger and more cohesive, and that those stronger family bonds curbed such urban ills as gang membership and youth violence. “The story of the little girl going home to get a gun sounds like something you’d hear about from 21st-century Detroit or Philadelphia, [instead of] early 20th-century New York,” Allen says. “When you see things that are similar [to what’s happening now] from the time when things were supposed to be different, [the interns] were able to see that that’s not really what’s happening. So we were able to rethink some things about our own understandings of the quote-unquote ‘progress’ or ‘state of the black community’ now.” The interns’ impressions may read like mere passing observations, but they can become seeds that lead to rigorous scholarship. “History will be rewritten because of what’s discovered in these archives,” says Benaderet. “Historians who are coming down the line now will be writing different stories because of what they find in this archive.”

Readers of the paper found an African-American urban culture and way of life ignored by the white press. Photo courtesy of the Afro-American Archive

Sometimes that history is personal. During the first week of the DPAAP internship, the students completed a weeklong training in archival theory and practice and African-American history, which included a trip to the National Archives and the Enoch Pratt Free Library. At that time, the Pratt Library had an exhibition about the Afro installed in its lobby cases. “It was crazy,” Mehlinger remembers. “We’re in the exhibit, and one of the girls, who was also an intern, said, ‘Hey, Mark, check this out. This dude has your last name.’” Mehlinger’s last name isn’t common among African-Americans; his great-great-grandfather was a Jew from Bavaria who married a former slave. Yet there in a display case was a letter from African-American historian and writer Carter G. Woodson to the publisher of the Afro asking the editors to uphold the high quality of its content. It was co-signed by a few other people, including one Louis R. Mehlinger. “My paternal grandfather grew up in Washington, D.C., and that would have been his uncle, I believe,” Mehlinger says. “I brought it up to my parents and my parents were like, ‘Yeah, Louis Mehlinger rented out a room to Carter G. Woodson in his house.’ And I was just like, wow.”

At that moment, Mehlinger found a connection to something he had never felt before. “Baltimore is still a place where I don’t necessarily feel at home because I don’t have an extended family here,” he says. “So being in the library and seeing a piece of my own history with this newspaper that I’m working on—out of the whole internship, that was the thing that stuck with me the most. Because no one in my family knew about it, either. They knew about my great-uncle knowing Carter G. Woodson, but they didn’t say, ‘Oh, you’ll probably come across him in the Afro archive.’”

That experience—that personal moment of interacting with the past—is a unique engagement with history that the archive offers. “There’s a great pedagogical potential here to develop courses that are not just going to discuss African-American history but are going to push the envelope and frontiers of what we know about that history,” Vinson says. “Because what’s in the archive is so new, so fresh, and really asks new questions of the past that we haven’t asked before.

“History comes down—it has an opinion, it’s a deliberate reading of the past,” Vinson continues. “I want us to keep in mind as we’re starting to make these moves toward this post-racial America that I think a project like this really keeps us anchored in the past and how we get to where we are. I think this is an important project that doesn’t let us forget the steps and missteps that have been taken along the way.” And the Afro archive “opens up the multiple possibilities of that rendering of history,” Vinson adds. “And I think that’s an important lesson. These students were giving order to experience. And I think the students who were able to participate in that certainly felt the gravitas of that, but I think we can harness that and through this project actually teach it.”

Dalrymple and Vinson hope to demonstrate that educational potential with DPAAP’s next phase. Hinderer is leading a spring 2012 undergraduate seminar that aims to get students to explore the Afro archive and develop their own research exhibitions using the materials. Tom Smith, a 2011 graduate of the Krieger School, has designed an open-sourced robot scanner that he aims to use to digitize 20,000 images from the Afro’s archive over the 2011–2012 academic year. And though the Mellon grant has ended, the project continues, thanks to a two-year extension funded by the Sheridan Libraries, the Krieger School’s Office of the Dean, and a Center for Educational Resources donor. The Johns Hopkins–Afro DPAAP team has assembled a steering committee to help them develop 10 online exhibitions using materials in the archive that might be of use to K–12 classroom curricula and undergraduate and graduate students over the next two years. They want to get teachers into the archive next summer to explore its classroom potential, but all future plans are dependent on funding.

The ultimate goal is to make the archive accessible to the community at large. “The stories that the interns told of how they felt as they opened up files and saw letters from individuals to other individuals trying to force certain kinds of civil rights activities, for example, they’re there as history is being created,” Dalrymple says. “It’s a visceral experience. We want other kids to have that. Here’s what they wrote. No one’s going to interpret that for you. You look at those words and you see what you think these people were saying and why they were saying it and you start to interpret it.”

Those are merely the first steps in exploring this vast ocean of primary sources. People’s sense of history gets shaped and molded every day. And often that does not mean reconsidering what has already been told, but getting a glimpse of a vast array of histories still to be written. “The way I look at it, this place, we are the custodians of about three or four different lineages of history,” Gartrell says. “There is the history of the paper itself that came out every week. Then there’s the history of what went into creating that paper. Then there’s the history of the people who worked for the paper, who contributed to creating that paper. And then there’s the history of the Murphy family itself—if there was no Murphy family, there may not be an Afro-American as it is today. So there are a lot of layers and places that you can go as a researcher, and it’s not just limited anymore to what came out in the paper. And that’s that layer of treasure.”

Bret McCabe, A&S ’94, is a senior writer at Johns Hopkins Magazine.

Access the archives online: