March 6, 2010 | by Dale Keiger

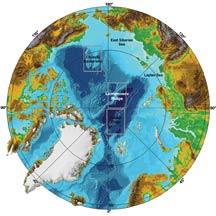

Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

Things are heating up in the Arctic

As the Arctic warms meteorologically, it has begun to warm politically. Norway and Russia have sparred over claims to the Barents Sea and economic exploitation of Svalbard. Canada and United States disagree over the Beaufort Sea. Canada and Denmark have traded barbs over a disputed speck of land off the Greenland coast called Hans Island. It’s easy to smile bemusedly at some of this—you can shop online for spoof merchandise from the Hans Island Liberation Front—but if the northern polar ice pack continues to melt, and most data indicate it will, disputes over territorial and economic rights in the Arctic will cease to be sources of humor.

Kurt D. Volker, managing director of the Center for Transatlantic Relations at the Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, cogently lists the issues that loom as the ice pack thins: “You have fishing. You have shipping and transportation. You have the environment. You have coastal security. You have indigenous populations. You have strategic security. You have energy exploitation. You have science, mineral rights, any number of things in which the Arctic Sea states have interests and overlapping claims.” Volker believes the United States has gone too long without asserting its own interests, “partly because we have more non-Arctic things to worry about. The Arctic for the U.S. is faraway northern Alaska. For Canada and Norway it’s much more integral to their sense of nationhood and identity.”

Most observers put oil and natural gas at the top of the list of potential disputes. No one knows how much fossil fuel might reside under the once-inaccessible Arctic seabed, but the U.S. Geologic Survey turned heads with a 2009 estimate of 40 billion to 160 billion barrels of oil, and 30 percent of all remaining undiscovered natural gas. (How anyone estimates a percentage of what’s undiscovered is a bit murky, nevertheless . . .) There are also deposits of iron ore, nickel, zinc, and gold. Merchant shippers covet a northern passage through polar waters because Yokohama, Japan, to Rotterdam, Holland, is 12,854 miles around Asia and through the Suez Canal; across an ice-free Arctic, it would be about 8,500 miles.

Five nations lay claim to territory in the Arctic: Russia, Canada, the United States, Norway, and Denmark (by way of Greenland, which is a self-governing administrative division of the country). Article 76 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (which the United States has never ratified because of opposition by a few U.S. senators) established a procedure for advancing claims on Arctic territory. One dispute concerns a 1,200-mile-long submarine structure called the Lomonosov Ridge, which Russia asserts is an extension of its continental shelf, and thus the basis for its claim to vast undersea territory. Not so fast, say the Danes—the Lomonosov is equally an extension of Greenland’s shelf.

Russia has been the most assertive of the Arctic claimants. In 2007, two Russian mini-submarines planted a titanium replica of the Russian flag on the seabed at the North Pole. Artur Chilingarov, a Russian presidential envoy, was quoted in the London newspaper The Telegraph: “Look at the map. All our northern regions are in or come out into the Arctic. All that is in our northern, Arctic regions. It is our Russia.” Observes Volker, “They have been dramatic, they’ve made extravagant claims, they are bold. It’s not worrisome per se. In some ways it’s natural. But it is an illustration of why we need to get our act together, and all the other Arctic states need to do the same.”

Volker estimates the Arctic states have about three to five years in which to negotiate agreements, before that starts to get significantly more difficult. “The longer you take, the more likely it is that energy companies and shipping companies and mining companies and militaries will be staking out their interests directly,” he says. “Then you have to negotiate from a position in which vested interests are in play.”

SAIS’ Center for Transatlantic Relations has launched an Arctic policy project, to bring together U.S. government and nongovernment stakeholders and provide an impetus for policy development. Volker says that initiative will occupy his next two years. His immediate recommendation is appointment of a U.S. special envoy to begin working on integrating American interests, what Volker calls “a huge sprawling mess” spanning the departments of Commerce, Energy, Transportation, Defense, and State, as well as federal agencies such as NASA and NOAA, and the U.S. military. Second, he would begin bilateral discussions with Canada to resolve some nettlesome issues over fishing rights and disputed waterways. Once that’s done, he says, the United States will be in a much better position to participate in a forum of the Arctic states.

On the other end of the globe, Antarctica was a frozen landmass that had never been

colonized, didn’t border any nation, and had nothing in the way of extractable resources.

An international agreement to preserve the continent as neutral territory for scientific research was not that difficult to negotiate. Regarding

the Arctic, Volker says, “All this was theoretical as long as things remained frozen. Now that it’s melting, it all becomes more real and a source

of competition.” —DK

Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

As the Arctic warms meteorologically, it has begun to warm politically. Norway and Russia have sparred over claims to the Barents Sea and economic exploitation of Svalbard. Canada and United States disagree over the Beaufort Sea. Canada and Denmark have traded barbs over a disputed speck of land off the Greenland coast called Hans Island. It’s easy to smile bemusedly at some of this—you can shop online for spoof merchandise from the Hans Island Liberation Front—but if the northern polar ice pack continues to melt, and most data indicate it will, disputes over territorial and economic rights in the Arctic will cease to be sources of humor.

Kurt D. Volker, managing director of the Center for Transatlantic Relations at the Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, cogently lists the issues that loom as the ice pack thins: “You have fishing. You have shipping and transportation. You have the environment. You have coastal security. You have indigenous populations. You have strategic security. You have energy exploitation. You have science, mineral rights, any number of things in which the Arctic Sea states have interests and overlapping claims.” Volker believes the United States has gone too long without asserting its own interests, “partly because we have more non-Arctic things to worry about. The Arctic for the U.S. is faraway northern Alaska. For Canada and Norway it’s much more integral to their sense of nationhood and identity.”

Most observers put oil and natural gas at the top of the list of potential disputes. No one knows how much fossil fuel might reside under the once-inaccessible Arctic seabed, but the U.S. Geologic Survey turned heads with a 2009 estimate of 40 billion to 160 billion barrels of oil, and 30 percent of all remaining undiscovered natural gas. (How anyone estimates a percentage of what’s undiscovered is a bit murky, nevertheless . . .) There are also deposits of iron ore, nickel, zinc, and gold. Merchant shippers covet a northern passage through polar waters because Yokohama, Japan, to Rotterdam, Holland, is 12,854 miles around Asia and through the Suez Canal; across an ice-free Arctic, it would be about 8,500 miles.

Five nations lay claim to territory in the Arctic: Russia, Canada, the United States, Norway, and Denmark (by way of Greenland, which is a self-governing administrative division of the country). Article 76 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (which the United States has never ratified because of opposition by a few U.S. senators) established a procedure for advancing claims on Arctic territory. One dispute concerns a 1,200-mile-long submarine structure called the Lomonosov Ridge, which Russia asserts is an extension of its continental shelf, and thus the basis for its claim to vast undersea territory. Not so fast, say the Danes—the Lomonosov is equally an extension of Greenland’s shelf.

Russia has been the most assertive of the Arctic claimants. In 2007, two Russian mini-submarines planted a titanium replica of the Russian flag on the seabed at the North Pole. Artur Chilingarov, a Russian presidential envoy, was quoted in the London newspaper The Telegraph: “Look at the map. All our northern regions are in or come out into the Arctic. All that is in our northern, Arctic regions. It is our Russia.” Observes Volker, “They have been dramatic, they’ve made extravagant claims, they are bold. It’s not worrisome per se. In some ways it’s natural. But it is an illustration of why we need to get our act together, and all the other Arctic states need to do the same.”

Volker estimates the Arctic states have about three to five years in which to negotiate agreements, before that starts to get significantly more difficult. “The longer you take, the more likely it is that energy companies and shipping companies and mining companies and militaries will be staking out their interests directly,” he says. “Then you have to negotiate from a position in which vested interests are in play.”

SAIS’ Center for Transatlantic Relations has launched an Arctic policy project, to bring together U.S. government and nongovernment stakeholders and provide an impetus for policy development. Volker says that initiative will occupy his next two years. His immediate recommendation is appointment of a U.S. special envoy to begin working on integrating American interests, what Volker calls “a huge sprawling mess” spanning the departments of Commerce, Energy, Transportation, Defense, and State, as well as federal agencies such as NASA and NOAA, and the U.S. military. Second, he would begin bilateral discussions with Canada to resolve some nettlesome issues over fishing rights and disputed waterways. Once that’s done, he says, the United States will be in a much better position to participate in a forum of the Arctic states.

On the other end of the globe, Antarctica was a frozen landmass that had never been colonized, didn’t border any nation, and had nothing in the way of extractable resources.

An international agreement to preserve the continent as neutral territory for scientific research was not that difficult to negotiate. Regarding the Arctic, Volker says, “All this was theoretical as long as things remained frozen. Now that it’s melting, it all becomes more real and a source of competition.”