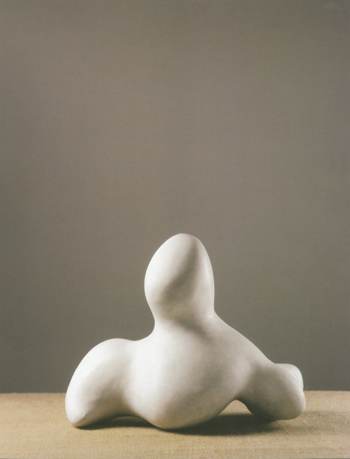

Jean Arp’s The Woman of Delos could help scientists discover how and why our brains respond to works of art. Photo Courtesy of Adler & Conkright Fine Art, New York

Beauty is in the brain of the beholder. Sure, the eye may appreciate lush colors and graceful lines, but the chain of command goes like this: The optic nerve delivers hues and shapes to the mind. Specific clusters of neurons fire off. And we experience pleasure, or some other sensation that satisfies our understanding of the hazy term “aesthetic.”

We know beauty when we see it. Scientists want to know when we see it too. A partnership between the Johns Hopkins Krieger Mind/Brain Institute and Baltimore’s Walters Art Museum will let scientists peer inside the brains of arts patrons to see what makes them tick. Among the questions researchers plan to explore: Where in the brain do certain shapes, such as smooth curves, register? Do we perceive them as “pleasurable” or not? And do our eyes seek out those shapes (or colors or lines) because our brains link them with the resonance and joy we associate with art?

As part of “Beauty and the Brain,” what the Walters is calling an exhibition and an experiment, museumgoers are asked to judge the aesthetic value of 10 sets of 25 images, many of them borrowed from aspects of The Woman of Delos, a sculpture by Franco-German artist Jean Arp. Viewers don cheap 3-D glasses, examine the images, then choose which images they find “most pleasing” and “least pleasing.” Each image is only slightly different from those surrounding it.

On the day of the exhibition’s January opening (it runs through April 11), reactions from a steady stream of the curious ranged from surprise at the prospect of taking part in an experiment to glee. A 4-year-old girl balks at putting on the glasses, while a middle-aged woman, talking to a friend, compares one of the Arp likenesses to a sculpture she made years ago. “I’ve been a docent at museums, but I’ve never seen anything like this before,” says another experimental subject, Heidi Price, a lawyer from Baltimore.

“I thought I’d do this because it was new.” Although the differences in shapes often aren’t enough to make meaningful aesthetic judgments, she says, Price found objects with large, open curves caught her eye. Like hundreds of others who passed through the museum’s space on opening day, she folded her answer sheet in half and slipped it into a slot in a clear square bin at the exhibit’s end.

The task for the Mind/Brain Institute is to collate the responses, then match them with a second phase of the experiment, in which another set of human subjects will be shown images, including of the Arp sculpture, while in a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner. In essence, the Walters part of the study allows researchers to narrow the possibilities for what might excite neurons in the brain. “We’ll show them shapes and see which cubes of tens of thousands of neurons fire up,” says Ed Connor, director of the Mind/Brain Institute and lead investigator of the study-in-progress. Not that neuro-researchers expect to find all of the answers. To a large extent, aesthetics is a function of nurture, not nature. There are learned behaviors, memories, and cultural issues that help us form aesthetic judgments—above and beyond how our neurons respond to art. “But some facets are subject to inquiry, like abstract sculpture,” Connor says. “Pure shape is what we’re after, to see how the brain deals with it.”

The work of Connor and others involves a nascent field called neuroaesthetics. Thirty or so years ago, scientists thought that computers might do their work for them by figuring out how we compute what we see. “But it’s a power beyond the power of computers,” says Connor, who has been studying how the brain processes images for 14 years. “Our ability to look at an infinity of objects and know instantly what each is is astounding.”

Previous studies at the institute involving MRI scans of rhesus monkeys identified regions of their brains that responded to the long, smooth curves of the Henry Moore sculpture Sheep Piece. That research found uniformity in the monkeys’ responses to bits and pieces of Moore’s work. The Mind/Brain Institute’s current project came to the attention of the Walters three years ago when Richard Huganir, a professor of neuroscience at Hopkins and co-director of the Johns Hopkins Brain Science Institute—a separate entity from the Mind/Brain Institute, and one that finances much of Connor’s work—introduced Connor

to Gary Vikan, the museum’s director. Vikan, who has long been interested in finding new ways to structure exhibits to enhance a museum patron’s experience, later heard Connor speak about the rhesus monkey experiments. Since then, his interest in exploring the connection between art and the brain has grown.

“Artists are intuitively neuroscientists,” Vikan says. “They’re constantly trying to find shapes that have an effect on viewers. Our goal is to see if there’s some norm out there—something similar to what the English art critic Clive Bell called ‘significant form.’ Are there certain shapes that are universal, maybe eternal, that artists are trying to tap? We all think we know them when we see them, but maybe scientists can find a neural basis for it all.”

Some artists have so far supported the idea of the research, Vikan reports. “I don’t think there’s ever any problem with knowing more about the world or how we humans perceive it,” says D.S. Bakker, a Baltimore artist and an instructor at the Homewood Art Workshops at Johns Hopkins. “Should artists learn what the most pleasing form is, many will go out of their way to disprove it. I seriously doubt that truly creative people would stop thinking outside the box just because someone found a new box.”

Regardless of how the Arp experiment works out, Hopkins is committed in the longer term to fleshing out the mostly blank canvas of neuroaesthetics. The Brain Science Institute will hold a symposium at Hopkins in the fall that will link artists with scientists to explore how your brain works on art. “There are a quadrillion synapses in the brain,” says Huganir. “The system itself is so beautiful that studying it doesn’t take away from the beauty and richness we experience while living it. The question we’re asking is a valid one: How do we derive such pleasure from using this very complex machine?”