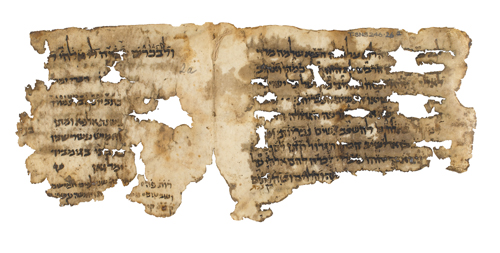

This bit of vellum from the Cairo Geniza was written in Iran early in the 10th century and contains the end of the biblical book of Nehemiah, vocalized with Babylonian vowel signs. Photo: Cambridge University Library T-S NS 246.26.2

Jewish tradition teaches that the Hebrew script, as the word of God, cannot be simply thrown away. Documents must be collected in repositories called genizah (sometimes transliterated geniza) for ceremonial burial. But whereas most genizot are cleared regularly, that of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Fustat (now old Cairo) piled up for centuries, perhaps because the attic storeroom was so large. This has made the trove of documents, which date primarily from 900 to 1250, an invaluable historical resource. Johns Hopkins associate professor of history Marina Rustow has spent years studying the Cairo Geniza, a daunting accumulation of almost 280,000 folio pages that are now dispersed among several U.S. and European libraries. The collection includes literature, letters, government decrees, petitions, marriage contracts, receipts, even children’s primers.

Central to her study is the idea that a community as a whole cannot be understood without paying attention to its margins. Her current manuscript-in-progress, Patronage and Politics: Islamic Empire and the Medieval Jewish Community, attempts to learn how the Fatimid caliphate (909–1171) functioned by studying its Jews, the empire’s smallest religious minority. The sheer task of governance in the premodern era, when communications were poor and populations sparse, is key, and the administrative texts found in the Geniza give clues to the Fatimids’ methods. One important tactic was “government from below,” in which the people themselves were responsible for petitioning the caliphate. In an article for the University of Cambridge’s Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, Rustow translated and examined such a petition from the khatib (preacher) of a mosque whose tenants—on which he depended for income and the mosque’s upkeep—were in arrears. She explains that the Fatimid caliphate issued decrees in response to petitions from anyone in the realm, in principle, though in practice from anyone with connections. “Petitions served as an administrative device and a check on abusive officials,” she says.

Although Rustow’s general area of Geniza research is Jews in the medieval Islamic world, other questions come into play. For example, some documents feature no Hebrew text at all. How did they find their way to the Geniza? Perhaps through a paper sale; after regime changes, the new rulers often sold off all the previous government’s archives as scrap. Rustow suspects, though, that the Fustat Jews kept certain texts around as templates—communication with the bureaucracy was highly stylized, and copying out or paraphrasing another’s rhetoric was good practice.

One challenge to Geniza study is the wide dispersion of the material. The majority is now housed at Cambridge. A nonprofit called the Friedberg Genizah Project has been tracking down and digitizing the documents and archiving them on one website. Rustow, with her curiosity about the afterlives of the texts, has mixed feelings: “If all I was interested in were the words on the pages, the digital reproductions would be fine, sometimes even better, because you can zoom in”—an advantage for deciphering centuries-old handwriting. But she sees the paper as more than a container for text, finding the material aspect of a manuscript likewise important; for example, a manuscript that’s never been folded is perhaps a draft, whereas one folded and refolded many times was likely copied and passed along, possibly over miles and years.

The collection contains a wealth of information about social and economic history—from detailed financial records to the power of women in Fatimid society. But the texts demand an uncommon linguistic skill set: Many of them are written in Judeo-Arabic, which is Arabic written in Hebrew script. “People wrote the language they spoke in the alphabet of their scripture,” Rustow explains. The ability to work in both languages is uncommon, Rustow says. She has it, which has heightened her sense of professional obligation to bring the material to light.