Of all the subjects to broach. Of all the things to bring up. Is there any better way to get people at each other than to ask them about God? Hordes have been dispatched to the Great Beyond, or at least the grave, over the issue of His nature, or whom He favors. Religion, in grand historical terms, has meant breaking out the slingshots and scimitars. In modern times, avid nonbelievers have added their (often loud) voices to the fray. You’d think the last thing a sensible, introspective person would want to do is get in the crossfire. Even if one were to write a thoughtful treatise that pleads for the moderate uses of religion in furthering the aims of humankind, he would risk becoming the enemy of the two poles of the U.S. culture wars.

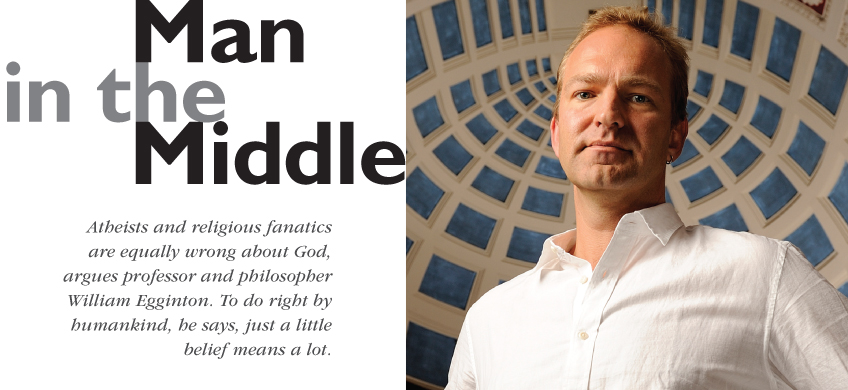

Yet that’s exactly what William Egginton has done. In his book In Defense of Religious Moderation, published this month by Columbia University Press, Egginton argues that fervent believers and nonbelievers share more than they’d care to admit: a certainty that goes beyond the bounds of reason and does little more than polarize people. Their ongoing metaphysical shouting match has real-world consequences, Egginton argues. It keeps society from moving forward.

A professor and chair of German and Romance Languages and Literatures at Johns Hopkins, Egginton is aware that he’s placed himself in the middle of a philosophical pissing match. He knows he’s asking for it. “Honestly, I do worry about how people might react,” says Egginton, a tall, elegant man with a warm demeanor and a ring in each ear. “I want this book to be part of the larger public conversation on religion. Instead of yelling at the TV, I wanted to say something thoughtful, to offer something.”

IF “MODERATISM”—A LABEL that has been applied to some politicians and a small but powerful bloc of voters in the fractious, turn-of-the-millennium United States—can actually be “impassioned,” then Egginton’s book earns the adjective. The author energetically defends the center position—and it’s not an easy gig. He argues that religion, practiced without the arrogance of ardor, has the power to make people do things that transcend self-interest. Even agnosticism, with its skeptical approach to religion, has value because those who embrace it recognize there are limits to human knowledge. They have doubts. They’re much less likely to claim they hold the only tenable metaphysical position, and that the rest of the world is wrong. They are more likely to be tolerant of people who aren’t like-minded.

In one light, Egginton’s (anti?) polemic can be seen as a defense of a conservative impulse. He is, after all, defending systems of thought that have existed for centuries without concrete proof that the main actor in them—God—has a genuine presence. In a river of modern academic liberalism, he is swimming upstream. “I don’t entirely shirk the notion that there is a conservative side to my argument, as long as we separate it from the political conservatism in the U.S.,” he says. “I base my argument in part on the suspicion of humanity’s ability to roll out grand plans,” such as those concocted by hard-line theocracies, secular dictators, and communist regimes. “Perhaps it is possible for humanity to be radical and cut off from its religious roots, but not entirely.”

He calls himself a political liberal, one motivated by pragmatism—the concentration on the solving of problems and not on adherence to ironclad concepts like Truth and Justice. Egginton says his argument has more to do with evidence sprinkled throughout the history of philosophy than his own beliefs. “The book is really about how I find religious moderation a defensible position philosophically,” he says. In clear language, Egginton muses about moderate religious thinking through the ages—mining Plato, St. Thomas Aquinas, Maimonides, and Leibniz. He focuses especially on the 18th-century moral philosopher Immanuel Kant, who in the Critique of Pure Reason questioned humanity’s ability to grasp the universe by being entirely logical.

“My rationalism leads me to look at the limits of reason,” Egginton says. “Kant warned us 250 years ago that reason runs into trouble when it oversteps its boundaries. I’m very scientific in my outlook. What I’m calling religious beliefs are things we don’t know or can’t know about. It’s about making a choice.”

His response to people who possess the passion of certainty: We can’t know. For Egginton, God is a metaphor for the ineffable, a symbol for what the mind can’t reach. We simply make an existential decision about whether to believe or not to believe. Those who can admit that they can’t ultimately know whether a supreme being hangs out in or above the cosmos, being acquainted with doubt, are more likely to be tolerant than those who reject outright the idea that there is a God. If you can’t admit we’re all clueless in the realm of metaphysics, then you’re likely, he thinks, to be part of the problem here: entrenched camps of religious fundamentalists and anti-theists that inflame the wrong kind of passions.

By distancing himself from the claims of either extreme, Egginton puts himself in a bit of an odd place and in a position that, at least initially, could be seen as weak by other thinkers. He sees value in not knowing, in preserving the religious customs based on not knowing, and in embracing what may in fact be a nonentity—God. He’s basing a lot on knowing that we can’t have knowledge of everything. In doing so, he says, he’s following a tradition that has led religious men to question their beliefs and to look to science for answers. For every Galileo burned at the metaphorical stake for heresy, there have been many more devout individuals in history, including Isaac Newton, who were free to use their religious belief to balance their quest for knowledge of the knowable, and did so.

Science hasn’t been hindered by a modicum of belief, Egginton posits. In fact, it has been aided by it, because of the limits of knowledge inherent in believing. “Moderate religious practice as well as much of the theological tradition have placed doubt at the very heart of faith,” Egginton writes. “The existence in my life of a realm of counterintuitive stories [in the Bible] making implausible claims to truth may well have strengthened rather than weakened my commitment to seek the truth in this world.”

Lines like those are bound to gall atheists, who often lay blame for religion’s durability not on extremists but on people who should “know better” than to believe in an interested, lone supreme being but who support churches—and the secular sins they (allegedly) commit—anyway. Folks who think like Egginton are frequently called out as “enablers” by hard-line atheist authors such as Richard Dawkins (The God Delusion), Sam Harris (The End of Faith), and Christopher Hitchens (God Is Not Great: How Religion Poisons Everything). In turn, it is those atheists on whom Egginton shifts the weight of his argument in In Defense of Religious Moderation.

Because Egginton uses those atheists as exemplars of ungodly thinking, many nonproselytizing atheists and secular humanists aren’t likely to recognize themselves in his critique. Atheists who took at least a quick peak at the book, pre-publication, say Egginton has painted the atheistic movement with too broad a brush. He is wrong, they say, to insist that nonbelievers, as a group, discredit the pious by claiming they believe the literal letter of holy books. Many of Egginton’s fellow academics are nonbelievers, and though his book is a tightly focused philosophical essay, and not a theological rallying cry, he’ll likely take heat for it. Some said they couldn’t bring themselves to intently read In Defense of Religious Moderation.

Here’s the terse dismissal of Egginton’s book by Daniel C. Dennett, a professor of philosophy at Tufts University and author of Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon: “Skimmed it. Not worth rebutting. It’s a mixture of sneering caricature and egregious misunderstanding. If this is the best critique of atheists as ‘fundamentalists’ that can be wrought, the defenders of agnosticism and ‘moderate religious beliefs’ are on the ropes.”

HE DOESN’T LOOK LIKE a glutton for whatever punishment God or man can mete out. Energetic but relaxed, and with a bearing that is open and accommodating, Egginton, 42, evinces the air of a hip young uncle whom junior family members love to visit. As he teaches a graduate-level course in New World Baroque, he veers seamlessly between speaking English and Spanish, applying his expertise at extracting interpretations from centuries-old Spanish literature and making them relevant to today’s art, fiction, film, and politics. He encourages his class, held with 11 advanced degree candidates and a couple of prospective grad students shopping for schools, to do the same. As good students do, they find shortcomings and contradictions in the class text.

At the head of a rectangle made of tables, Egginton is all length and angles, a rangy realm of locomotion topped with an oblong face. A towering forehead is fringed with short blond hair. He looks a bit like a mash-up of Sting and Bill O’Reilly. Today, he wears an orange zip-up fleece shirt with a red rectangle on it—a Rothko painting made functional.

The son and stepson of academics and a teacher-turned-lawyer, Egginton spent part of his early years in South America, learning to speak Spanish as well as English while his dad traveled the back roads of Colombia to research his doctorate on land reform. Young Bill proved to be a quick study. As he grew older—living in Louisville, Kentucky, and then with his mother in Arlington, Virginia, after his parents’ divorce—his interest in languages expanded. (He would eventually learn to speak and read five of them—English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish—fluently.)

His family attended Catholic services early on. His father, Everett Egginton, a socialist and agnostic, thought that Billy should understand religion. But the young student was a believer, though one who began asking tough questions when he reached middle school. Certain Catholic concepts, such as transubstantiation (the conversion of a glass of wine into the blood of Jesus Christ and a small bit of Styrofoam-like carbohydrate into his body), floored him. “He told me, ‘I can’t believe that wafer is a piece of bread, much less the body of Christ,’” Everett Egginton remembers.

As his inquisitiveness grew, so did his number of interests—everything from chess to tennis to Shakespeare to advanced math—to the point that his parents wondered about his wanderlust. Billy followed such a wide range of interests that, like an overstretched piece of elastic, he threatened to split apart at the center. “Of course, I worried about him,” says his father, the longtime dean of international and border programs at New Mexico State University and now a professor of education there. “I saw this huge potential, but I wondered what exactly Billy would do with it.”

Everett Egginton saw something of himself in his son: an enthusiastic generalist set in relief by the Western world’s penchant for specialization. “I’ve struggled with finding that center,” he says. “As I look back, it has worked out. Maybe being uncomfortable isn’t a bad way to make your way through the world. If you look at it metaphorically, walking is being off balance.”

Bill Egginton staggered on to become his high school class valedictorian and gave his speech on—shocker!—the importance of being moderate to an audience at Washington’s Constitution Hall, touting the value of consensus and compromise to solve problems, his father recalls.

Although Bill had set out on a path to study math or science, possibly pre-med, Dartmouth College offered more opportunities for undergrads to travel than most schools. With his father’s taste for revolutionary movements in Latin America and for seeing the world, Egginton saw a chance to take his education international. A German opera course taken as a sophomore confirmed his decision to switch to the humanities, the Valhalla of the generalist.

With political theory and literature as his quarry, a vision of a life not unlike his father’s began to form. Trips to Ecuador, France, and Spain followed, as did a return of sorts to Latin America. Bill decided to visit his father and stepmother in El Salvador during the summer between his junior and senior years to research his undergraduate thesis on revolutionary poets and writers. Because of an ongoing brutal war, Bill was forced to stay to the north, in Guatemala City, where he rented a room in the back of a poor family’s compound. The son of the woman who ran the place regularly reminded him that a young American student wasn’t welcome there. One day, cops robbed him of his passport. “At its heart, Guatemala City was a very violent place,” he recalls.

He further immersed himself in languages as a grad student at the University of Minnesota and then by seeking a doctorate in comparative literature at Stanford. Blending intense language study, literary theory, media, and philosophy, comparative literature pushed all of Egginton’s intellectual buttons. So did an Austrian Romance philologist, a fellow member of a Stanford philosophy study group, whom Egginton gave a lift home one night on the back of his motorcycle. She was amazed that the guy she was forced to wrap her arms around was so stereotypically American—cowboy boots, leather jacket, even the earrings.

His caricature belied an active, worldly mind, Bernadette Wegenstein recalls. The two later married, and both taught at SUNY-Buffalo. Egginton and Wegenstein, now a research professor of German and Romance languages at Johns Hopkins and the director of the university’s Center for Advanced Media Studies, came to Homewood in 2006.

These days, the William Egginton family is religious but in a predictably judicious way. Egginton, Wegenstein, and the couple’s three children, ages 11, 8, and 3, are Catholics. But piety isn’t exactly in huge supply in their Baltimore home. Egginton might attend church now and again. “It’s rare. I try to go to what Jews would call the High Holidays,” he says.

Still, he and his wife are skeptics. “For all of the Catholic Church and its horrible faults, and there are many”—here, Egginton ticks off a list that includes the Church’s restricting a woman’s right to choose an abortion and proscribing condom use during the AIDS crisis—“I love the ritual of the ceremony, the smell of the incense, the stopping of time. Even though I’m a liberal and often progressive in my thinking, I’m impressed with the anchor of time that is part of religion.” It’s been more than 20 years since he took confession, but he’d like to try it again soon, he says. “I could see putting myself before the question of guilt and forgiveness.”

The children should have some idea of what religion means, Wegenstein adds, even though religion in the United States often does not always live up to the lofty standards of forgiveness and altruism. “It’s a bit of a weak spot because we’re not sure where it’s all going,” Wegenstein says. “And they want to be like us and not spend much time at church. But it’s still the right thing to send them off to Sunday School.”

Such considered, almost cautious devotion angers atheists, who argue that those who practice a faith that they question provide cover for those who don’t ask questions about their beliefs. “Moderate religion enables fundamentalism by providing aid and comfort to the basic belief that supernaturalism really is OK,” says Gregory Paul, an author of several academic journal articles on religion and its relation to economic health. The more religious a country is, Paul contends via his sociological research, the more likely it is to be beset by socioeconomic ills, including inequality and violence. He took a quick read of Egginton’s book before it was published. “Basically, [Egginton] thinks that it is best for people to worship and love a creator that has one way or another slaughtered and denied free will to countless billions of innocent persons,” he says, adding that studies show atheists to be more ethical than people who tag themselves as “very religious.”

Like Dennett, Paul bristles at Egginton’s portrayal of militant atheists. “He does the usual trick of claiming that assertive atheists stereotype all Christians by in turn stereotyping assertive atheists,” Paul says. “He contends that assertive atheists have to make all Christians into ideological Bible literalists. I’m not aware of a single, well-known atheist who does that. We are quite aware, for example, that Catholics who make up half of Christendom are not literalists.”

FROM THE VIEW OF his office’s small dormer window, a peering hole cut from the roof of Gilman Hall and pointed south, Egginton can espy much of the Homewood campus, a good bit of the sturdy progressivism of downtown Baltimore, and the old steeples that poke up around its edges. Farther away, and through a good bit of haze, he can make out the poor man’s Golden Gate Bridge—a span named after Francis Scott Key, the moderately religious author of “The Star-Spangled Banner” and former vice president of the American Bible Society—which crosses the Patapsco River just before it spills into the Chesapeake Bay. Egginton shakes off such facile interpretations of his place in the world. He’s not an academic atop an ivory tower. “It’s brick,” he quips.

But he knows the argument. A lofty, cloistered academic tells less-privileged people how to believe. Who should care? “The ivory tower criticism is a valid one,” he says. “Even the metaphor of climbing down the stairs to be with the people might not be entirely apt. But by trying to teach myself how to write for a larger audience, I’ve sharpened my thinking. I’m challenging myself to make a crystalline point. That means I have to very precisely understand what I think.”

Not that Egginton isn’t already out in the world. He is well published, contributing several philosophy-based columns to the erstwhile New York Times blog The Stone, regularly submitting to academic journals, and penning five previous books on the philosophies and interpretations present in everything from Argentine magical realist writer Jorge Luis Borges to ethics, psychoanalysis, Spanish literature, and the theater. All were academic books, replete with precise but specialized language likely to be understood only by students of philosophy and comparative literature. He hopes In Defense of Religious Moderation, constructed as if by a very well-read nonacademic thinker and for lay readers, introduces him to a larger audience. He’d like the book to ensconce him in the world of the public intellectual, a realm of celebrity in Europe but populated by few in the egghead-wary United States. He’s not all that fond of the term, either, though he wants to have more of a stake in public debate than the typical academic. “I wanted to write a book that wouldn’t have the tag ‘impenetrable’ on it,” he says.

He writes it at a time when high-profile religionists, such as Pat Robertson, and self-styled messiahs, such as the Mormon Glenn Beck, are on the wane and when religious belief is dwindling. Despite highly publicized battles over books and teaching evolution in schools, a declining number of Americans attend church or claim to follow a religion. Egginton doesn’t dispute that. But he sees his argument, which could be viewed by skeptics as a default one, as a sensible philosophical answer to an age-old question.

“The argument I’m making is that this possible nullity—God—represents our limitations, temporally and spatially,” he says. “We have this drive to transcend. It’s part of our being. It’s an ineradicable metaphysical desire. It’s not that you can’t be rational about it. It’s an existential decision, one I take responsibility for. I respect that people like Christopher Hitchens make a choice as well.”

Only time will tell if his voice will get out there with the big boys, like Hitchens’ has. He pursues a higher profile against some steep odds, say others who have worked with Egginton. Americans haven’t exactly been charitable to public intellectuals. “I think if he worked in Europe he would constantly be in the newspapers and in TV debates,” says Santiago Zabala, a research professor at the ICREA/University of Barcelona, and a colleague. He adds that In Defense of Religious Moderation, the Spanish-language edition, will be published under the guidance of Manuel Cruz, an important philosopher there. “Perhaps we will be able to steal Bill from you,” Zabala adds.

His father emphasizes where Egginton hopes to interpolate himself on the theological and political continuum—right in the scrum of things. “He’s going to love being there,” Everett Egginton says. “It will put him in the middle of the conversation.”

Michael Anft is Johns Hopkins Magazine’s senior writer.