When Edmond Baganizi, SPH ’11, explored Baltimore by bus, he was moved by the poverty he saw. “Poverty is one of the things that make people more prone to violence here, just like in Rwanda,” he says. Baganizi feels that connection in his bones.

As a child in Rwanda, he and a few of his siblings would leave their home to watch planes descend from the clouds near their village, “a peaceful place” just east of Kigali, Rwanda’s capital, and its international airport. The family raised cows and led a quiet life. One day, young Edmond ran outside to check out noise he thought came from jet engines. But what he was hearing was a cacophony of gunshots, and the harbingers of a disaster. A day or two later, the government told people to stay home. Radio announcers, stirring up hate by using bogus racial distinctions that dated back to when the country was run by its Belgian colonizers, told Hutus to kill Tutsis, sometimes naming those they thought should be killed. Those Hutus who didn’t follow orders were themselves targeted.

Over the course of the next six months, Baganizi, two young brothers, and an 8-year-old neighbor who bore scars from machete attacks ran from militia men who tried to kill them, hitched rides from one camp for displaced persons to another, hid among corpses in plundered homes, and worried for their families. They finally made it home after members of the Rwandan Patriotic Front saved them.

Baganizi told his story to a Bloomberg School of Public Health class one night and broke down in tears. “I started to get emotional during my talk, and this man from Baltimore who had lost his brother, and who had been shot 12 times himself, stood to talk to me,” he says. “He told me it’s normal and healthy to go back into your memories when you talk about violence.”

When the Bloomberg School sought new ways to study the nature of violence as part of a recurring graduate course, it stayed close to home. What would happen, educators asked last December, if they used the course, called Children in Crisis, to start a dialogue among one-time Baltimore gang members, the city’s victims of crime, and the school’s Rwandan students?

The results of the course’s new emphasis, educators say, were dynamic and poignant, and will likely lead to an ongoing series of conversations among Baltimore community members about how they can overcome the bloodshed that has racked their neighborhoods. Both the handful of conversations on violence and the course itself took a cross-cultural look at the conditions that underpin and herald violence. “We’re already seeing a demand to expand these conversations to kids in more neighborhoods and to another college,” says Daniela Lewy, SPH ’06, a research associate in international health at the school and a teacher of the course, which focuses on the cultural and political forces that place children at risk worldwide. She adds that the course has grown to include how violence affects people of all ages, and not just children.

To develop the course, Lewy and other Bloomberg professors turned to Baltimoreans affected by violence—either as victims, family members of victims, or perpetrators. They also tapped graduate students in public health, including Rwandans Lorraine Beraho, SPH ’11, and Baganizi. “When we first started exploring this, we thought, ‘What possibly could connect the violence in Baltimore with what happened in Rwanda?’” says Beraho. “But we found those connections. The only real difference is that Rwanda was an acute violent situation while Baltimore is chronic.”

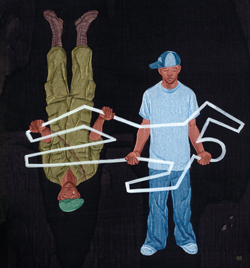

She and other course designers developed themes that would find points of intersection between the two cultures, as well as explore assumptions each makes about violence. Besides providing catharsis and communion among speakers, the course provided students and facilitators with the opportunity to explore the common face of violence. Language prevalent during the Rwandan genocide—members of the Tutsi minority like Baganizi were slurred as “cockroaches” and “snakes”—was compared to the use of the term “nigger” as a precursor to violence in the United States. “It’s an old white term of derision that you now see used on the street by blacks who want to do violence to each other,” says Selwyn Ray, one of the facilitators of the conversations and executive director of Big Brothers Big Sisters of Maryland. Adds Baganizi, “You can see other signs—the language of violence in some extreme forms of rap music, the stop-snitching campaigns. People who grow up in those harsh conditions without mentors—that’s a warning sign, too.”

Using his experience as a guide, Baganizi exhorted Baltimoreans to get out in front of their violence problem, particularly the desire to avenge one harmful act with another. “Of course you want a perpetrator to be punished, but a community still needs reconciliation,” he says. In Rwanda, special local tribunals—called gacaca (and pronounced ga-cha-cha) courts—were formed to judge accused murderers during the genocide. “They are there to make sure people can live together and overcome the violence together,” Baganizi says.

Baganizi has lived that idea: During the height of the genocide, he and his brothers considered joining a militia to punish those who had killed and maimed. But instead of focusing his anger on hurting the guilty, he turned it toward helping people heal. “My main objective became saving lives,” he says. He became a licensed medical doctor in Rwanda in 2009 and hopes to study and treat childhood diseases. “My thinking is that if people are healthy, perhaps they’ll be more likely to work together. And if they do that, maybe they’ll be more tolerant.”