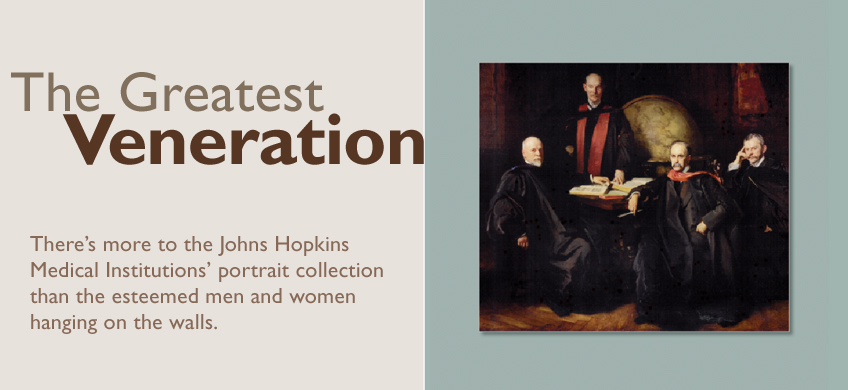

John Singer Sargent’s Four Doctors looms over the West Reading Room of the William H. Welch Medical Library at the School of Medicine like a daunting challenge. The mammoth 1907 painting depicts Howard Atwood Kelly, William Stewart Halsted, William Osler, and William H. Welch, the school’s founding clinical faculty. They were considered the best of their day, and they were recruited to help the school become great. Sargent painted these men in a way that not only captured the school’s ambition but exalted the men themselves. They’re rarefied—a national anthem high note that few mere mortals can hit.

The portrait also kicked off the tradition of the Medical Institutions honoring their own. The collection contains 325 portraits at last count—mostly paintings but some photography and sculpture, too—and features faculty from Johns Hopkins Hospital and the School of Medicine, School of Nursing, and Bloomberg School of Public Health. It includes works by notable American artists—Sargent, Cecilia Beaux, William Merritt Chase, William Draper, Jamie Wyeth—as well as regional artists like Thomas Corner, Ann Didusch Schuler, and Raoul Middleman.

This collection is loosely overseen by Nancy McCall, director of the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, and her staff. She has been the director since 1987 and with the Medical Archives since it was created in 1978 to document and preserve the Medical Institutions’ history, which includes the portraits. Early on, McCall says the Medical Archives staff conducted a room-by-room, closet-by-closet inventory to determine just what the hospital and the schools had. It was a meticulous task that revealed a few conservation headaches—such as radiator paint touching up some old gilt frames—but in that process, they were able to suss out the individual stories behind the history.

In those background anecdotes the subjects of the collection become more approachable. These stories illustrate that before these men and women were part of the esteemed few—the pioneers of a surgical technique, the basic scientists who figured out something previously unknown—they were doctors tackling problems that had eluded their expertise and knowledge.

The portraits are commissioned, and funding remains a mercurial process. Every year, on average, anywhere from two to four new portraits are being worked on and added to the collection. The Medical Archives doesn’t oversee this process, although it can certainly offer assistance. But who gets chosen for a portrait and how it gets paid for are questions that are up to individual departments and, sometimes, private individuals, who may decide to commission a portrait for a doctor who treated a friend, relative, or loved one. A revered university donor and her friends commissioned the two Sargent portraits that started the collection, and their back stories touch on the egos, politics, and fussiness behind the pigments.

LONDON’S TITE STREET extends but a few blocks through the Chelsea borough and practically runs directly into the Thames from the north. Today it’s a narrow lane lined with brick buildings. Shortly after it was created in 1877, though, some of its more colorful residents gave the street an unconventional air. It was Oscar Wilde’s preferred neighborhood when he resided in London on and off in the 1880s and 1890s. Expatriate American painter James McNeill Whistler occupied a flat at No. 33 Tite Street, which Sargent moved into in 1885. The year before, Sargent became a succès de scandale when he exhibited his Portrait of Madame X in Paris, and his reputation blossomed in London. Henry James would come to visit. Sargent was commissioned to paint President Theodore Roosevelt. And his studio became the destination for society ladies, countesses, and duchesses who wanted to be immortalized on canvas.

It was into this somewhat bohemian setting that the School of Medicine’s 50-something chief benefactor entered when she came to sit for her portrait in the early part of the 20th century. Mary Elizabeth Garrett was the only daughter of Baltimore and Ohio Railroad president John Work Garrett. Proving she had a head for business, she worked with her father for a spell. She befriended other affluent and educated Baltimore women—proto-feminist Martha Carey Thomas, English professor Mary Gwinn, activist Elizabeth King, and the self-educated Julia Rogers—who co-organized the Women’s Medical Fund Committee in 1890 to raise the money to form the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine on the condition that it admit women on an equal basis as men. Two years of financial and political negotiations with the university’s board of trustees ensued, resulting in the board requesting a $500,000 endowment to start the school. Garrett contributed a big chunk—$306,977—that came with the caveats that there must be coeducation and strict admission guidelines. The School of Medicine officially opened in October 1893 with an inaugural class that included 15 men and three women.

People close to Garrett worried that her largesse would be overlooked. “I guess a number of people among her friends were concerned that nothing had been done to honor her,” McCall says. “There wasn’t a plaque, there wasn’t anything.”

Some of Garrett’s friends, chiefly Thomas, commissioned Sargent to paint Garrett’s portrait. The 58-by-38-inch painting, which cost $5,000 (more than $100,000 today, as estimated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Consumer Price Index Inflation Calculator), features a seated Garrett wearing a black dress with her gray hair pulled back, resting her left arm on a table. Sargent often favored the dark colors of Dutch masters, and were it not for the white shawl accented with red flowers draped over Garrett’s shoulders and white gloves on her lap, the portrait’s dominant hues would bring to mind a Flemish pub’s ceiling.

The splash of color and the shawl’s gentle flourish were Garrett’s requests. She and Thomas were in London to view the portrait and felt it made her look too harsh. So they went shopping—returning to Sargent’s studio with the shawl, gloves, and flowers and asking him to brighten the picture up.

It worked—the shawl and flowers counterbalance the portrait’s seriousness, softening Garrett without diminishing her status as one of the pre-eminent philanthropists of her day. The portrait was unveiled in the rotunda of the Johns Hopkins Hospital October 4, 1904. “She was so touched, she commissioned Sargent to do this large group portrait of these four physicians,” McCall says.

In many ways Sargent’s Four Doctors reinforces our vision of doctors today. Clad in academic gowns, three of the four sit at a table in a dignified room. A few books, symbols of learning, rest on the table. The men look dignified, competent, well educated, and capable. They also look like refined gentlemen of a certain caliber.

That stature wasn’t always the norm, and it certainly wasn’t the customary context when Sargent painted The Four Doctors. Although medicine was certainly a skilled practice in the 19th century, it hadn’t yet evolved into the highly expert profession it is today. As journalist and professional skeptic H.L. Mencken noted, Halsted was “one of the first surgeons to employ courtesy in surgery, to show any consideration for the insides of a man he was operating on. The old method was to slit a man from the chin down, take out his bowels, and spread them on a towel while you sorted them out. Halsted held that if you touched an intestine with your finger you injured it and the patient suffered the effects of the injury.”

Sargent turns these four doctors into great men by subtly tweaking Grand Manner portrait traditions—particularly the attitudes of Rembrandt’s Syndics and Frans Hals’ Regents of the Old Men’s Almshouse—to represent men of knowledge. Unlike Thomas Eakins’ famed medical portraits, The Agnew Clinic and The Gross Clinic, Sargent’s painting doesn’t capture the doctors at work in a surgical gallery. Instead, it emphasizes their intellectual prowess. He paints them in their robes. The seated Welch rests his hand on a 1515 copy of Petrarch (which now resides in the Garrett Library at Evergreen Museum and Library), while Halsted stands behind him with one hand magisterially on his hip. All wear calm and confident expressions. Sargent included an immense Venetian globe in the background, which suggests not only the global reach of their knowledge but reinforces its magnitude through the globe’s size.

Not all of the doctors were pleased with it. Letters from Osler’s wife to her mother from this time report that Osler appreciated his likeness, Halsted and Kelly less so. Infamously, Sargent permitted Welch to wear his Yale robe but wouldn’t let Osler wear his Oxford red sash on color grounds alone.

Nevertheless, the finicky Sargent knew he was work-for-hire. In a letter to Welch dated June 10, 1926, Sargent wrote: “I am glad you have had good reports of the picture, which certainly has found great favor. Miss Garrett herself, before whom I always feel like a rabbit in the presence of a boa constrictor, has seen it and is pleased.”

THE PROCESS HASN’T changed much in 100 years. The Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins, for instance, maintains its portraits in an ornate room in the Wilmer Building at the institute. Lining the walls are the past chairs of Ophthalmology, starting with Frank Salisbury’s portrait of William Holland Wilmer, who retired in 1934, followed by Edward Longley, Alan Churchill Woods, Arnall Patz, and Morton Goldberg. The current chairman, Peter J. McDonnell, will be painted when he prepares to step down.

This custom is one of the ways portraits are added to the collection. It started with a few major figureheads, and it became tradition that department heads would be painted when they stepped down. And then certain notable figures and personalities started to be added to the collection, too. “In the early decades,” McCall explains, “as certain figures gained special prominence, their portraits were painted, but it was because money had been raised for it.” Funds get raised “every possible way. They’re anonymous. It comes out of some kind of departmental funds or special endowment and so forth. It just happens.”

Once funding is secured, the actual process is fairly straightforward. The department or doctor chooses an artist, a fee is determined, sitting sessions are planned out, and a deadline is given. Every portrait gets sent to the archives to be photographed, measured, appraised, and cataloged. Each portrait typically gets presented to the public twice—once by the department and once at the School of Medicine’s biennial alumni celebration.

This process often permits the artist to get to know the person being honored, not merely spend time studying his or her likeness. For the portrait of pediatrician and geneticist Barton Childs, Maine artist Judy Taylor says she read some of his articles before coming down to visit him in his office. “We had a very lovely conversation for a couple of hours, just the two of us,” Taylor says. “I like to talk to my sitters, just to get a sense of their personality, not really to talk about the painting, just to talk about what they do. We talked a little bit about art because he had traveled quite extensively. He liked to go visit historical churches all over the world.”

During this meeting Taylor noticed a number of photos and pictures on the walls of his office. She had recently completed a mural about labor history for Maine’s Department of Labor building, in which she used a black-and-white montage sequence in the background to tell a story, and she decided to use a similar approach to give a sense of Childs’ personality throughout his life and career. “One of the black and whites [photos] in the background is him as a younger man leaning back in his chair with his feet up on a drawer that opened from his desk,” Taylor says. And he still sat that way when she met him, when he was in his early 90s. “His feet were up on that desk drawer just like in that picture, and you could see on that drawer where his feet had been. He had worn it down.”

Taylor painted his portrait in her Maine studio, but she returned to Baltimore to show Childs the portrait, and again to attend its unveiling, which also served as a memorial; he died February 18, 2010, at the age of 93. Department or biennial unveilings provide an opportunity for the greater Johns Hopkins community to socially celebrate and honor their colleagues, and Childs’ memorial provided Taylor with a greater appreciation of just how influential her sitter had been—proof of why people suggest one of their own for the portrait treatment. “I came down for the memorial service, which was also part of the unveiling,” Taylor says. “And I heard all the tributes of his students—one was in her 70s, one was in her late 20s. So, to me, I felt like he was this giant in medicine.”

Selected portraits and the stories behind them

Arguably no single portrait in the collection more succinctly captures its subject than this modest, dignified likeness of Vivien Thomas. The nondegreed but surgically skilled Thomas had been surgeon Alfred Blalock’s lab assistant for roughly a decade when Johns Hopkins recruited Blalock to be its chief surgeon in 1941. When Blalock teamed up with pediatric cardiologist Helen Taussig to discover a way to treat blue-baby syndrome, Thomas was given the daunting task of recreating the condition in canine test subjects and experimenting with the surgical strategy for treatment. (Read more)

________________________________________________________________________________

The Division of Neuroimmunology and Neurological Infections is dedicated in honor of Richard Johnson, but the pioneering neurologist also owns another distinction: His portrait is one of the few painted by a Johns Hopkins alumnus. Raoul Middleman, A&S ’55, who earned his bachelor’s degree and then promptly set out to work as a Montana ranch hand, picked up drawing when he entered the Army in 1957. (Read more)

________________________________________________________________________________

According to Nancy McCall, Helen Taussig didn’t appreciate this portrait by now revered painter Jamie Wyeth—perhaps because it reminded her of a difficult moment in her life. Taussig spent nearly four decades working in pediatric cardiology at Johns Hopkins Hospital and more than 50 years teaching in the School of Medicine, where, in 1959, she was only the second woman to be named a full professor. When she retired from the hospital in 1963, the pediatric cardiology faculty and fellows commissioned her portrait. (Read more)

________________________________________________________________________________

The most striking thing about Judy Taylor’s portrait of Barton Childs, a pediatrician and geneticist who died in 2010, isn’t just how dramatically different it is from other portraits in the collection but how unique it appears even in the context of Taylor’s work. A talented if conventional painter of colorful landscapes, still lifes, and portraits, Taylor turned for this painting to an almost Lucian Freudian palette of matte grays, black, and white, with a subtle, peachy pink animating her subject’s face and hands. (Read more)

________________________________________________________________________________

When Owsei Temkin died in 2002 a few months shy of his 100th birthday, Johns Hopkins didn’t just lose the man who helped build its Institute of the History of Medicine; the medical history field lost one of the scholars who helped shape it into a discipline. “He was one of my mentors,” McCall says. “I am deeply fond of him.”

McCall used to visit him during his final years when he lived in a retirement community, and though he had the body of a nonagenarian, his mind remained as sharp and nimble as ever. (Read more)

________________________________________________________________________________

Looking back, advertisement and magazine illustrator Bernie Fuchs was the ideal choice to capture overachieving cardiac surgeon Denton Cooley. Cooley, a student of Alfred Blalock, successfully implanted an artificial heart into a patient, was the first surgeon to remove pulmonary embolisms, developed artificial heart valves, started the Texas Heart Institute in his native Houston, and in 1968 made the cover of Life magazine for being part of the first U.S. surgical team to transplant a human heart. (Read more)

________________________________________________________________________________

It was the men of this era who appear formidable in Beaux portraits, standing with straight backs and clad in dark colors. Unless, of course, the female sitter happens to be as accomplished, intelligent, and driven as Mary Adelaide Nutting, in which case she is depicted as seen here: as a woman who looks so unflappably confident, pity the man who underestimates her. (Read more)

________________________________________________________________________________

With a career at the School of Hygiene and Public Health (as the Bloomberg School of Public Health was known prior to its 2001 name change) that spanned six decades, it seems fitting that occupational health and industrial hygiene pioneer Anna Baetjer would be painted by a member of an artistic family whose relationship with their profession was similarly devoted. Baetjer, who in the 1960s established one of the first research programs in environmental toxicology, was painted by Cedric Egeli, whose father established a modest portrait dynasty. (Read more)

________________________________________________________________________________

An infectious disease specialist and dean of the School of Medicine for 24 years, Alan Chesney also wrote the first history of the medical school and hospital. (It was his mentee, Thomas Turner, who possessed the fundraising skills and diplomacy that brought the schools of medicine, nursing, and public health together with the hospital to archive their collective history—now called the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives.) From 1943 to 1963, Chesney compiled his three-volume history, which is a timeline of the Johns Hopkins Hospital and School of Medicine from 1867 to 1914. (Read more)

________________________________________________________________________________

The Department of Art as Applied to Medicine, which was founded by German émigré Max Brödel, celebrated its centennial this year as the first medical illustration program of its kind. In the era before affordable and immediate photography, Brödel’s illustrations were in heavy demand by Johns Hopkins faculty for their anatomical correctness and exquisite realism, doing to the inside of the body what John James Audubon did for birds. But Brödel was more than a serious artist; he was a close friend of H.L. Mencken and member of the Saturday Night Club, where the pair would heartily eat, drink, and play the piano. (Read more)

________________________________________________________________________________

Surgeon, librarian, and hospital planner John Shaw Billings was a 19th-century renaissance man who did everything from serve as a Union army battlefield surgeon during the Civil War to help unite New York City’s libraries into the New York Public Library. In 1876 he was one of five men asked by the Johns Hopkins Hospital Foundation to submit design plans for the as-yet-unbuilt hospital. His plans were selected, and he oversaw construction alongside the Boston architectural firm Cabot and Chandler and Baltimore architect John R. Niernsée. (Read more)

Bret McCabe, A&S ’94, is a senior writer for Johns Hopkins Magazine.