The interrogation room was bare except for a few metal chairs, and its tan walls looked as if they hadn’t been painted in decades. A single transom window stood cracked open slightly, but it couldn’t relieve the room’s stuffy air. Outside, beyond view, lay the hot, dusty streets of North Africa.

The prisoner—identified by the CIA as a top al-Qaida official—sat motionless, his salmon jumpsuit stretched across a middle-aged paunch. Glenn Carle, SAIS ’85, a career CIA spy, knelt before him. “We do not have much time,” Carle told the prisoner, whom he refers to by the code name CAPTUS. “The situation is changing.”

It was autumn of 2002, and Carle had been interrogating the man for weeks. During that time he’d gained the prisoner’s trust, using the same skills he’d honed as a case officer when he manipulated foreign nationals into revealing their countries’ secrets. Carle schmoozed, he chastised, he cajoled . . . whatever it took to ingratiate himself.

By now, CAPTUS answered most of Carle’s questions freely—and, as far as Carle could tell, honestly. But there were a few key matters the prisoner wouldn’t discuss. And Carle’s superiors at CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, were running out of patience.

Carle urged CAPTUS to come clean. The man had already been kidnapped by American agents off a Middle Eastern street and rendered, in the parlance, to this foreign jail, his whereabouts known only to his captors. He was being held in solitary confinement, without charge or explanation. And unless he revealed everything he knew about al-Qaida, Carle told him, his situation would get even worse: “You will be taken to a much, much nastier place.”

CAPTUS clenched his hands together so hard that his fingers turned white. He tried to object, but Carle wouldn’t listen. Carle needed CAPTUS to change his mind. If he didn’t, Carle knew, they’d both soon be transferred to a so-called black site, part of a secret network of CIA-run prisons where the most dangerous terrorist suspects were held.

Carle had two reasons for hoping to prevent the transfer. For one thing, he had serious doubts about the legality of the interrogation techniques then in use at the black sites. But his other reason was darker still. During their daily conversations, Carle had come to believe that CAPTUS was not the top terrorist the CIA accused him of being. Yes, he had done business with al-Qaida but only because he’d had no choice. CAPTUS was like “a small shop owner who is doing business with the mob,” Carle says. And now, the man feared admitting any contact with the terror network, lest he provide the grounds for his own execution.

In nightly cables back to headquarters, Carle conveyed his mounting concerns about the case. But his orders kept coming back the same: Press him harder.Carle believes that, after years of painstaking surveillance—and in the heightened emotions of the post-9/11 world—the CIA bureaucracy simply wouldn’t consider the possibility that they’d gotten the wrong man.

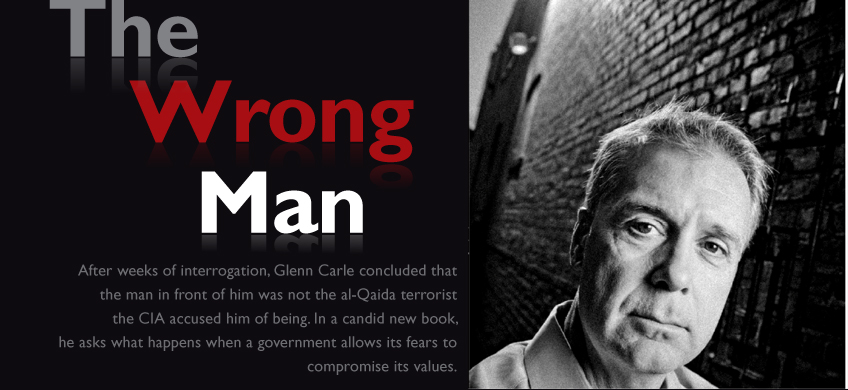

TODAY, GLENN CARLE IS a recognized expert on antiterrorism. Retired from the CIA since 2007, he writes essays and appears on panels organized by think tanks such as the New America Foundation on the nature and reach of al-Qaida. In May, when headlines trumpeted Osama bin Laden’s killing, the New York Times was among the news outlets that turned to Carle for comment.

Then in July, Carle made headlines of his own, publishing The Interrogator: An Education (Nation Books), a damning memoir of his involvement in the CAPTUS case. Unusually candid in its portrayal of the CIA’s internal workings—and the toll the agency’s moral gray zones take on its operatives—Carle’s book sparked a new discussion on the excesses of the global war on terror. Though the agency has made no formal response to the charges raised in the book, some loyalists have mounted a whispering campaign claiming that Carle is misinformed about the CAPTUS case—or, worse, that he’s lying. Then, too, Carle also faces criticism from opponents of the CIA’s actions: that his confessional memoir is too little, too late.

As an agent, Carle was sworn to secrecy about whom he met and what he did. Everything he ever writes about the CIA must pass through an agency board of censors, who slashed about 40 percent of his original manuscript for The Interrogator, excising whole chapters and leaving scenes largely blacked out. To a lay reader, the book is baffling in places; one reviewer called it “by far one of the most frustrating books I have attempted to read in years.” But despite the challenges and criticism, Carle says, he felt he had to come forward. “I worked in, and know about, significant issues of national concern,” he says. “The public should know what we are doing—and most particularly, what we have done to ourselves.”

Since 9/11, the CIA has rendered at least 150 terror suspects, capturing them on foreign streets and spiriting them off for imprisonment in other foreign countries. (Because these operations are covert, their exact number is unknown.) Empowered by the so-called torture memos of 2002—secret White House documents that authorized severe “enhanced interrogation techniques” for these prisoners—CIA agents subjected many to treatment widely considered torture, including sleep deprivation, cramped confinement (with or without an insect), and even, in a few cases, waterboarding.

The root of this policy, some experts now say, was an outsized fear of al-Qaida as a coordinated, worldwide army of terrorists. “In the post-9/11 hysteria, we assumed the worst,” says counterterrorism expert Marc Sageman, principal of Sageman Consulting. “We thought these guys were 10 feet tall, and that they knew far more than they did know.” In fact, he adds, though al-Qaida was and remains a virulent threat, its reach was always limited, with few ties to the patchwork of regional terrorist entities worldwide with which it was once conflated.

Fear caused Americans to betray their own ideals, Sageman argues. By implementing punishments considered too cruel for convicted U.S. criminals, “we did engage in collective hysteria, to the point that we are threatening American values.”

CAPTUS WOULDN’T BUDGE, DESPITE Carle’s pleadings. And so, as Carle recounts in The Interrogator, the CIA airlifted both men to a rocky, desolate moonscape of a country. (Carle won’t name it, but clues in the book point to Afghanistan.) There, CAPTUS was held in a U.S.–run prison Carle calls “Hotel California”—a dank, freezing warren of pitch-black passageways, where heavy metal music blared round the clock to agitate and disorient the inmates.

When Carle next saw CAPTUS, the prisoner lay chained on the floor of a windowless, 10-by-6 cell with a heavy steel door. He had one small blanket to protect him from the bone-chilling cold. Instead of a salmon jumpsuit, CAPTUS now wore faded, ratty pajamas that were much too small for him—clothing purposely chosen by his captors to humiliate him, Carle says. And CAPTUS’ face bore marks of mistreatment, though CIA censors won’t allow Carle to describe or explain them. “He looked awful,” Carle recalls now. “He was a complete mess. I was horrified.”

The change in CAPTUS’ attitude, Carle says, “was instantaneous, dramatic, clear, and as I had forewarned. He was miserable and terrified and furious.” Carle tried to make things easier on the prisoner—for example, by arranging for a second blanket—but there was little of substance he could do.

Over the following two weeks, CAPTUS grew less and less cooperative. He denied knowing people Carle knew that he knew. He claimed ignorance of events he’d actually been involved in. During one heated exchange, Carle asked CAPTUS about an issue that was “not fundamental” to his mission, he says. Even though the stakes were low, CAPTUS belligerently refused to answer.

“What are you doing to me? This is horrible,” CAPTUS spat. “I’ll never tell you. You can kill me.”

Carle never saw CAPTUS physically tortured. But as he watched his human connection with the man deteriorate during the prisoner’s psychologically brutal confinement at Hotel California, Carle became convinced that such techniques were “not just cruel and futile but counterproductive,” he says.

Though he didn’t know it at the time, FBI interrogators had already come to the same conclusion. That agency had been questioning suspects for decades, and its traditional strategy is to build rapport with the suspect and seek common ground, not to alienate him with threats or abuse. As top FBI interrogator Ali Soufan has revealed, traditional interrogation techniques led to crucial early al-Qaida revelations such as the identity of the 9/11 attack’s mastermind, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. “There was no actionable intelligence gained from using enhanced interrogation techniques [during that interrogation] that wasn’t, or couldn’t have been, gained from regular tactics,” he wrote in a 2009 New York Times op-ed. “In addition, I saw that using these alternative methods on other terrorists backfired on more than a few occasions.”

SITTING AT THE WOODEN TABLE in the Bethesda, Maryland, Barnes & Noble where he does all his writing, Carle is explaining how he first got into the spy business. At 55, his easy bearing marks him as a lifelong athlete—Carle’s hockey and football exploits earned him a spot in his high school’s athletic hall of fame—and he has the down-tilted eyes and unlined cheeks of a world-weary imp, part Paul McCartney, part Regis Philbin.

After graduating from Harvard and studying international relations in France, Carle took a job with an international bank—“the standard path for a Harvard graduate,” he says wryly. Feeling stifled, he soon quit the bank’s training program without a plan and moved back into the 14-room Victorian house in Brookline, Massachusetts, where he’d grown up. “I’m at home, waiting on tables, thinking, holy shit, I’m 25 years old. What am I going to do?” he recalls. Casting about for a profession that would challenge him “intellectually and morally, and maybe even physically,” Carle hit on diplomacy, then espionage: “I thought, being a spy—that must be wild. Why don’t I try that?”

Carle enrolled at the Nitze School of Advanced International Studies and majored in European studies, with the goal of joining either the Foreign Service or the CIA. In the end, he got both jobs, doing diplomatic work at U.S. embassies as a cover for his clandestine work. It was as a “diplomat” in Paris in the late 1980s that he met his wife, Sally, a Brit. When, four years later, Sally accepted Carle’s marriage proposal and he confided his true profession, she laughed. “You, a spy?” she asked. To Sally, Carle was an absentminded professor. “If he can’t remember three things at the supermarket,” she asks now, “how could he possibly be a spy?”

Carle admits to a certain distraction about some of life’s details. Along with being a certified jock—he still works out daily—Carle is a compulsive reader who favors the classics and science fiction. (He has read the Lord of the Rings trilogy nine times so far.) “I will forget appointments because I’ll be reading Plato,” he says. Moreover, Carle suffers from another constitutional handicap: According to those who know him best, he doesn’t like to lie. “Glenn’s the all-American boy,” says one college friend. “He’s honest to the point of being impolitic.”

The duplicity required to talk foreigners out of their secrets came hard to Carle. “It was a bit against the grain of my personality,” he says. With practice, though, he learned the seductive art of asset recruitment—befriending useful foreign nationals and manipulating them to his country’s ends. “I exploited people’s deepest hopes, won their deepest trust, so that they provided me what my government wanted,” he writes in his memoir.

Carle wasn’t trained as an interrogator—at the time, no CIA case officer was. Before 9/11, holding and questioning prisoners wasn’t part of the agency’s portfolio. But Carle was a skilled case officer with superior language skills. What’s more, he spent years working on counterterrorism before 9/11. So when CAPTUS was rendered, Carle got the call.

REVELATIONS ABOUT BRUTAL questioning techniques were made in press reports in 2005, and public pressure forced the Bush administration to put a stop to enhanced interrogation. When President Barack Obama took office, he repudiated the methods as illegal. But some architects of the Bush war on terror continue to argue for their efficacy—a fact that drives Carle batty. Shortly after bin Laden’s death, he recalls, “keepers of the Bush administration flame” took to the airwaves to claim that the success was due to intelligence gathered during enhanced interrogations—a claim for which there’s no basis, many experts say. “They’re just utterly shameless,” sputters Carle. “But I shouldn’t be surprised at that. It’s all malarkey. The facts as I understand them are that the critical piece of information was obtained a year after enhanced interrogation ceased.”

According to journalist Jeff Stein, a former Army intelligence officer who writes a blog called SpyTalk, the persistence of a faith in torture makes The Interrogator a welcome addition to the literature. “A lot of people really still believe that torturing people is the best way to get valuable evidence,” he says. “If another book comes out that offers a firsthand rebuttal of that view, that’s good. That’s valuable.” (It was Stein who first reported that John Kiriakou, an ex-CIA case officer who in 2007 broadly asserted the quick efficacy of waterboarding in the interrogation of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, had recanted his claims.)

But Carle says that renouncing enhanced interrogation is not the only goal of the book. Even if the worst excesses have ended, the CIA still holds an unknown number of prisoners in foreign jails without charge, along with other uncharged prisoners held by the U.S. military. In 2008, the Supreme Court ruled that detainees at the Guantánamo Bay detention camp in Cuba, many there since 2001, had a right to file habeas corpus petitions: lawsuits requiring the U.S. government to present valid reasons for their detention. Since then, 200 such petitions have been filed, and at least 38 prisoners have been released. But prisoners at other foreign sites—including an estimated 1,700 men, mostly Afghan fighters, held at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan—have no right to habeas corpus, the courts have ruled.

AFTER 10 WEEKS WITH CAPTUS, Carle was replaced by a colleague ordered to keep the case going at all costs, Carle writes. He says he can’t remember his last meeting with CAPTUS, but he knows that when he left, he didn’t say good-bye. Carle spent his last night crafting two final, blistering cables to headquarters pleading for CAPTUS’ release, but he never heard a word about them.

Carle has had no further contact with CAPTUS. He followed the prisoner’s case, though, when it emerged in the press. In the mid-2000s, a human rights group filed a writ of habeas corpus on CAPTUS’ behalf, but it was denied because he was not a U.S. citizen on U.S. soil. Then, sometime last year, “he was let go, with an apology from the U.S. government,” Carle says with a snort of contempt. “It corroborates every point I made when I was handling the case. It’s a sorry tale from beginning to end.” Though the erstwhile interrogator is barred by CIA oath from revealing the name of his prisoner—“I’ve never said his name, even to my lawyer,” Carle claims—journalists have identified him as Haji Pacha Wazir, an Afghan moneylender captured in Dubai in 2002 and released in February 2010.

Carle argues that each terror suspect still held should be allowed to petition for his freedom—both for humanitarian reasons and for the preservation of American ideals. “The foundation of Western civilization is habeas corpus,” Carle says. “It’s a big deal to keep someone chained to a wall in the dark for eight years, uncharged.” An assault on the rights of anyone, even our enemies, threatens us all, he argues. “Americans assume we are in some way intrinsically above state failure,” he says. “But Hobbes wrote that the mantle of civilization is very thin. It’s easily torn off, so that one is left a shivering, feeble soul, exposed to the harsh elements.”

The government’s justification for holding these prisoners is that they are enemy combatants who can be detained until the end of the war on terror—whenever that may be. Although President Obama has improved the process allowing prisoners to petition for release, he has also reaffirmed the country’s right to hold some prisoners indefinitely without charge.

CARLE SERVED FIVE MORE years in the CIA, retiring as deputy national intelligence officer for transnational threats. He now lives with Sally and their two teenagers in a handsome gray clapboard house near downtown Bethesda.

Since his book appeared, he says, the one question everyone asks him is why he didn’t leave the CIA after his wrenching experience with CAPTUS. It’s something that could be asked of any case officer at any time, he responds coolly: “The work of a case officer is often murky and morally ambivalent. One has to accept that operations will frequently run counter to one’s personal wishes.”

But when he retired and was able to speak out more publicly, his mind returned to CAPTUS. He knew that by writing a book about the case, he was opening himself up to criticism for not speaking sooner, for failing to free the prisoner. He also knew he faced a backlash from the agency, potentially harming his chances of finding consulting work in the field, a common second career. But he felt that the story needed to be told. “At some point, one has to say, ‘No, enough,’” says Carle.

The CIA’s press office did not respond to requests for comment on The Interrogator. But it did comment on an accusation Carle made in the New York Times in July. In that story, Carle charged that the Bush White House asked the CIA to provide personally damaging information about one of its critics, a University of Michigan professor. Carle objected to the request and believes he shut it down. CIA officials admitted to the Times that the White House had inquired about the professor but denied that it sought sensitive personal information.

“I was surprised that they acknowledged anything,” says Carle, who adamantly stands by his account.

Carle is not the first former spy to write about his time in the clandestine service. But his book is unusual in its attempt to depict the agency’s internal workings so directly, says David Ignatius, a columnist for the Washington Post: “It’s rare to see a book this honest about what’s under the skin.”

Valerie Plame Wilson, the former CIA operative whose cover was blown by the Bush White House after her husband, Joe Wilson, challenged the administration’s justification for going to war with Iraq, says Carle’s book surprised even her. “Joe and I had seen the lengths to which the administration was prepared to go to twist facts to fit preconceived conclusions,” she says. “But I had not understood how pervasive that attitude was within the bowels of the bureaucracy. It really is the banality of evil.” In a blurb for the book, she and Wilson jointly write, “This is a damning story, and a nation of laws would demand an investigation into whether crimes were committed.”

But Carle is not calling for a criminal investigation. What he’s calling for, he says, is the truth. “Vengeance doesn’t strengthen justice,” he says. “The only way you guard against individuals in power wrapping themselves in the flag and subverting institutions that are supposed to embody the flag is to cast light on the dangers, because human nature will not change.”

Margaret Guroff, A&S ’89 (MA), is a magazine editor in Washington, D.C.