Arguably no single portrait in the collection more succinctly captures its subject than this modest, dignified likeness of Vivien Thomas. The nondegreed but surgically skilled Thomas had been surgeon Alfred Blalock’s lab assistant for roughly a decade when Johns Hopkins recruited Blalock to be its chief surgeon in 1941. When Blalock teamed up with pediatric cardiologist Helen Taussig to discover a way to treat blue-baby syndrome, Thomas was given the daunting task of recreating the condition in canine test subjects and experimenting with the surgical strategy for treatment. Thomas performed the procedure on dogs so many times that when Blalock first used it on a human in 1944, he had Thomas talk him through it.

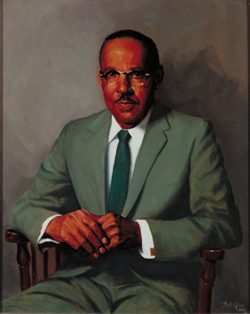

Thomas remained the expert in the background for the next three decades, working as the supervisor of one of Johns Hopkins’ surgical research laboratories. He retired in 1979, and during that last decade at the hospital the recognition that eluded him most of his life finally arrived. He was awarded an honorary degree by the university, appointed to the surgical faculty, and in 1968 this portrait was commissioned by a coterie of his former students. In the portrait, a bespectacled Thomas sits with his hands gently clasped in front of him, the picture of the polite Southerner he was. Nothing in the portrait telegraphs his achievements—the surgical techniques and instruments he developed, the countless heart surgeons who gained their confidence watching his deft hands. Even the portrait’s artist, Bob Gee, remains inscrutable, as the Medical Archives hasn’t been able to locate him. There’s just the dapper Thomas looking ahead with a sphinxlike calm.