March 6, 2010 | by Guido Veloce

Why do expensive hobbies inspire silly names?

Prompting that question was a midwinter professional trip to a warm place with a stay in a hotel next to a marina. Never having spent time next to a marina, I was fascinated by the yachts—by their price (entry level seemed to be $750,000); by the fact that none of them ever left the harbor; and especially by their names. They ran the gamut. There were risqué ones (Miss Behavin’ and Wet Dreams). There were unfortunate juxtapositions—The Broker of Venice was docked next to Paramour; Therapy was next to Outlaw and near Psycho Ward. A few didn’t sound especially good if you thought about them too closely. A Quiet Heart, for instance, can be a symptom of death, and the person who named Waterloo probably knew more British history than British slang. (Try separating the syllables “water” and “loo.”) Other yacht names suggested potential legal problems—would you want to pass the harbor patrol in Bacchus? Lady L is problematic if your spouse is Lady G. Finally, some yacht names were just plain baffling—was Tycoon, one of the smallest in the marina, named in a fit of post-modern irony or just downsized?

At first, I thought this might be an aberration. It was, after all, California. A little research on yacht names put that idea to rest. Surfing the Internet for the international used-yacht market turned up Global Warming (steer clear of ships named Greenpeace); Séance (why go to sea to talk to dead people?); and Moon Sand (say what?). One name sounded less like a yacht than a cry for help: Protect Me from What I Want. Among the most prosaically named yachts was the U.S.S. Williamsburg, an exception that may prove the rule. It was once Harry Truman’s floating White House. Now at $2,500,000, it awaits major repairs and rechristening, perhaps as, to paraphrase Truman’s famous aphorism, The Bucks Stopped Here.

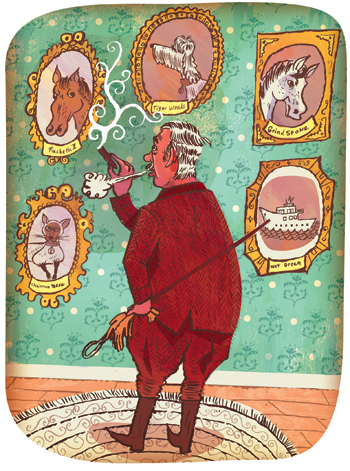

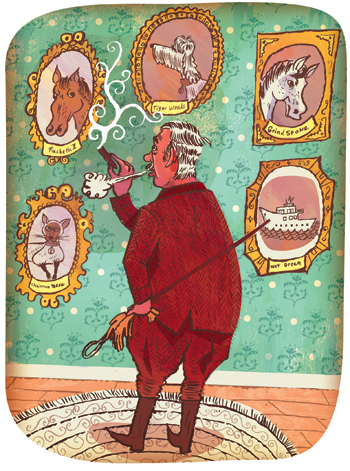

Once I quit perseverating about yachts, I realized that it isn’t just boats but rather expensive hobbies that inspire silly names. Consider racehorses and dog-show winners. Cats probably also belong on the list—a good thing about the passing of the 1960s is a sharp reduction in kitties called Chairman Meow. For now, however, I will stick to thoroughbred horses, with a quick glance at show dogs.

Looking at winners of the most famous horse races, you will find the occasional properly descriptive name. Foolish Pleasure, Genuine Risk, and Spend a Buck, for example. But you will also find bizarre literary allusions: Macbeth II (wouldn’t trust him) and Aristides (a wild and wacky ancient Athenian), along with Editor’s Note and Caveat, neither of which implies speed or excitement. Nor, for that matter, do horses named Birdstone, Deputed Testimony, or Grindstone, winners all. Then there are the unfathomable names, most recently Mine That Bird.

Maybe the point is that horses’ names bear little relation to their performance or much else. I can empathize with another winner, Go for Gin, but wouldn’t bet on anything more likely to stagger than run. It’s similarly hard to imagine Pensive winning a Kentucky Derby (he did). In a nautically rational universe a Seabiscuit—nasty food for sailors—wouldn’t outrank a War Admiral. Thanks to a bestseller and Hollywood, we know how that turned out.

Then there is the Westminster Dog Show. In the interest of space, I will simply note that it is the only conceivable competition, athletic or otherwise, in which an older guy called Stump can beat a younger, larger rival named Tiger Woods. Case closed.

We will know that the final days are near when the owner of the good ship Money Pit wins the Kentucky Derby with a horse named Kevin.

Guido Veloce is a Johns Hopkins University professor.

Why do expensive ho bbies inspire silly names?

bbies inspire silly names?

Prompting that question was a midwinter professional trip to a warm place with a stay in a hotel next to a marina. Never having spent time next to a marina, I was fascinated by the yachts—by their price (entry level seemed to be $750,000); by the fact that none of them ever left the harbor; and especially by their names. They ran the gamut. There were risqué ones (Miss Behavin’ and Wet Dreams). There were unfortunate juxtapositions—The Broker of Venice was docked next to Paramour; Therapy was next to Outlaw and near Psycho Ward. A few didn’t sound especially good if you thought about them too closely. A Quiet Heart, for instance, can be a symptom of death, and the person who named Waterloo probably knew more British history than British slang. (Try separating the syllables “water” and “loo.”) Other yacht names suggested potential legal problems—would you want to pass the harbor patrol in Bacchus? Lady L is problematic if your spouse is Lady G. Finally, some yacht names were just plain baffling—was Tycoon, one of the smallest in the marina, named in a fit of post-modern irony or just downsized?

At first, I thought this might be an aberration. It was, after all, California. A little research on yacht names put that idea to rest. Surfing the Internet for the international used-yacht market turned up Global Warming (steer clear of ships named Greenpeace); Séance (why go to sea to talk to dead people?); and Moon Sand (say what?). One name sounded less like a yacht than a cry for help: Protect Me from What I Want. Among the most prosaically named yachts was the U.S.S. Williamsburg, an exception that may prove the rule. It was once Harry Truman’s floating White House. Now at $2,500,000, it awaits major repairs and rechristening, perhaps as, to paraphrase Truman’s famous aphorism, The Bucks Stopped Here.

Once I quit perseverating about yachts, I realized that it isn’t just boats but rather expensive hobbies that inspire silly names. Consider racehorses and dog-show winners. Cats probably also belong on the list—a good thing about the passing of the 1960s is a sharp reduction in kitties called Chairman Meow. For now, however, I will stick to thoroughbred horses, with a quick glance at show dogs.

Looking at winners of the most famous horse races, you will find the occasional properly descriptive name. Foolish Pleasure, Genuine Risk, and Spend a Buck, for example. But you will also find bizarre literary allusions: Macbeth II (wouldn’t trust him) and Aristides (a wild and wacky ancient Athenian), along with Editor’s Note and Caveat, neither of which implies speed or excitement. Nor, for that matter, do horses named Birdstone, Deputed Testimony, or Grindstone, winners all. Then there are the unfathomable names, most recently Mine That Bird.

Maybe the point is that horses’ names bear little relation to their performance or much else. I can empathize with another winner, Go for Gin, but wouldn’t bet on anything more likely to stagger than run. It’s similarly hard to imagine Pensive winning a Kentucky Derby (he did). In a nautically rational universe a Seabiscuit—nasty food for sailors—wouldn’t outrank a War Admiral. Thanks to a bestseller and Hollywood, we know how that turned out.

Then there is the Westminster Dog Show. In the interest of space, I will simply note that it is the only conceivable competition, athletic or otherwise, in which an older guy called Stump can beat a younger, larger rival named Tiger Woods. Case closed.

We will know that the final days are near when the owner of the good ship Money Pit wins the Kentucky Derby with a horse named Kevin.

Guido Veloce is a Johns Hopkins University professor.

bbies inspire silly names?

bbies inspire silly names?