For the last 25 years of his life, Elliott Hinkes, A&S ’64, Med ’67, fed a ravenous appetite for the history of knowledge by collecting more than 300 rare books, pamphlets, and articles of science. An oncologist in Los Angeles, Hinkes grew to be as much a student of the works of scientific masters as an amasser of them. When he began to suffer from cancer himself, Hinkes reduced his patient load and signed up for graduate science courses. “I now find myself taking a number of astronomy and physics courses at UCLA to keep up with my collection, all of which has been a good way to stay young,” he wrote in an introduction to an exhibit of his books, held at the Eisenhower Library in 2004.

Hinkes succumbed to his disease in November of last year, leaving his trove of books to the Sheridan Libraries at Johns Hopkins. The Hinkes Collection ranks as one of the foremost gatherings of science books in the world, valued at $2 million, and as one of the largest ever amassed by one individual. “The collection is a mirror of what Elliott Hinkes valued and thought about,” says Earle Havens, curator of early books and manuscripts at the Sheridan Libraries. The collector was also fastidious about what he bought, Havens adds: “He was one of the few collectors to purchase complete, first edition texts that were in especially fine shape.”

Each volume lays out time-tested theories; most deal with the workings of the universe. But the collection presents viewers with a narrative arc that traces the history of applied reason. “As a scholar of modern science, these books constitute my research lab,” says Maria M. Portuondo, an assistant professor of the history of science and technology at the Krieger School. “They represent the whole sweep of science during the era of printing and even before.”

The scientific godfathers of the Enlightenment make up the collection’s bulk, but it also includes works by ancient Greeks—Archimedes’ writings on mathematics, Aristotle’s musings on the heavens, and Euclid’s Elements of Geometry. Modern genius is well represented, too. Fourteen books or original offprints of journal papers by Einstein, including some of his works on relativity, are included, as are a handful of writings by astronomer Edwin Hubble, including a first edition of 1936’s Realm of the Nebulae inscribed by the author to novelist Anita Loos.

“What’s great about this collection is that you not only see the development of science but the development of the technology of publishing,” adds Havens. “We’re teaching the history of ideas by using these books. We’re able to show students how knowledge was disseminated.”

For him and others charged with finding meaning in the Hinkes Collection, subtext and context vie with the science for attention. There are stories behind the stories, including the sad tale of Antoine Lavoisier, who wrote the first comprehensive primer on chemistry, then was guillotined during the Reign of Terror. Or the underlying flavor of Benjamin Franklin’s 1760–1764 writings on electricity, in which Portuondo can almost taste an era. “The Enlightenment character is in there, in a no-nonsense, very American way,” she notes. “It says, ‘Anyone can try these experiments.’”

The Sheridan Libraries will use the books to help teach undergrads about the march of science. It hopes to present a major exhibit of Hinkes’ dogged pursuit of history sometime in the fall of 2011 at the Peabody Conservatory’s library, to honor his widow and son.

“All truths are easy to understand once they are discovered; the point is to discover them,” Galileo once said. The Dr. Elliott and Eileen Hinkes Collection of Books of Scientific Discovery affords its viewers a chance to rediscover those truths straight from the minds that proved them, and to muse over the settings in which each of them happened. Here is a small sampling.

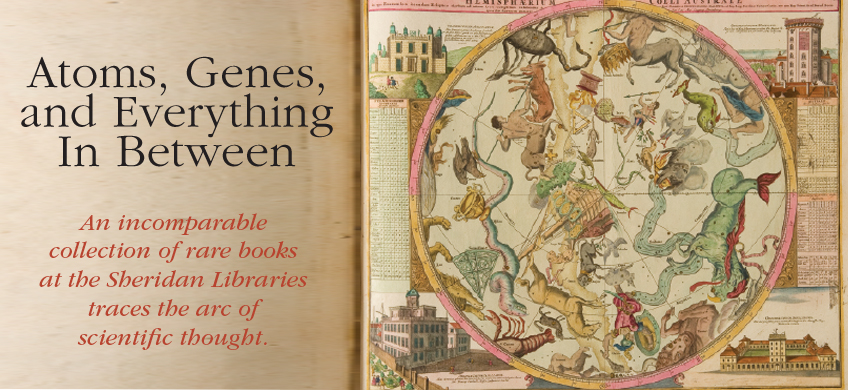

Johann Gabriel Doppelmayr, Atlas Coelestis (Celestial Atlas), 1742

The ornate, colorful map of the stars put together by Doppelmayr, a physicist, astronomer, and professor of mathematics in Germany, is the Hinkes Collection’s display piece, its museum offering. That’s largely because as much as the book includes several competing views of the cosmos held at the time—ancient astrology side by side with the sober astronomy of Tycho Brahe, Nicolaus Copernicus, and others—it also qualifies as a work of art. To supplement the dozens of detailed astronomical plates Doppelmayr had prepared, the book’s publisher included classic, colorful renditions of gods and goddesses, cherubs and other mythic creatures, and famous scientists and their observatories. “They hired an artist to paint everything,” says Havens. “My guess is there were no more than 1,000 copies of this made at the time. Before the age of mass production, books were rare as soon as they were published.” Perhaps because of the presence of art, not everything in the atlas is the product of reason. Cherubs playing with a telescope are looking not at the stars but at an elegant rendering of Diana, the Roman goddess of the moon. “There’s this playful element to it,” says Havens. Not that the import of its science should be overlooked. The book, with its various theories competing for space, reflects “the era of natural philosophy,” Havens says. “This was what was happening then, this conversation about what was possible. This humanistic, not purely scientific perspective of the universe was still alive.”