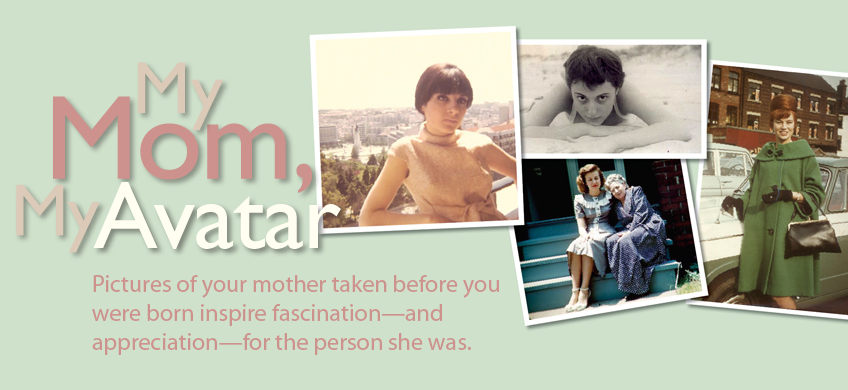

If you Google search “Piper Weiss”—and I shamefully do, often—a photo of my mother comes up. She’s got blunt black bangs and a mustard-colored wool frock. Her smoky eyes look just past the camera. Taken on the balcony of a Portuguese hotel, the city square and the roofs of buildings in the background, the photo has that sepia overlay like it was put through that Hipstamatic iPhone app that turns everyday photos into instant nostalgia.

It is my hope that anyone who stumbles across the photo online alongside my name assumes the snapshot is ironically vintage, technically modern, and actually me. I want to be mistaken for my mother, at least on the Internet. On my online account profiles, from Twitter to gChat, I’ve replaced my own portrait with one of my mother at 24. If you were to explain that to my mom, she’d be flattered but also have no idea what you were talking about. Her interest in technology stopped at recording TV movies on VHS tapes. All she knows is that several photos of her in her 20s are all over cyberspace. Fortunately, she’s OK with it.

Last year, I found two old photo albums in a cabinet at my parents’ house. My mother has always been our family’s archivist, maintaining bookcases full of vacation and birthday party pictures from the past 35 years. I know all of those photos by heart. But these two albums were new to me. They are a chronicle of her life between the ages of 21 and 24, after she’d graduated from college and before she married my dad, and there isn’t a single shot of me in either book. That may have been what made them so fascinating, at first.

Then I noticed her style. She wore stovepipe pants, minidresses frothing over with lace bibs. In one photo she’s wrapped a tribal headband around her bangs. In another, she’s posing in a fez. “I got that hat in Morocco,” she explained as I turned the page to find her riding a camel in a yellow bell-bottom jumpsuit. I have not known my mother to take a plane ride longer than six hours, much less swim in a pool, so this development was a shock.

The alarm bells continued at the sight of countless shaggy “beatniks” at her side who were not my dad. Not to mention the black “I Dream of Jeannie” wig, a pair of non-prescription glasses, a pet parakeet balancing on her head.

She curated each photo with facts that spoke not only to a time in her life but also a time in history. “In 1968, a week in Europe was affordable for a single woman with a day job in Manhattan,” she explained as I ogled a picture of her on the balcony of a hotel in Cannes. I also learned her version of a knockoff was having a tailor hand-make a design based on a picture she had ripped from a magazine during a trip to Italy. Wigs were commonplace; so were friends who were travel agents.

Compelled to share the photos with my friends, I scanned a few and posted them on a blog I created called My Mom the Style Icon. A few months later, the site caught on, and I began receiving submissions from adult children around the world. Photos of mothers from the 1930s through the 1980s told the story of their lives in the B.C. era (before children). Their styles ran the gamut, from the handmade to the haberdasher-crafted. One mom straddled a motorcycle in a halter top and headscarf in the California desert. Another wore shiny pink pants to the disco every Friday night as a young woman in the Philippines. Some rebelled by dressing in menswear for their prom. Others sported trademark beehives that took an hour to construct every day before school. While the looks, eras, and locations varied, the reactions from spawn submitting the photos were fairly unified. They were proud. After years of being embarrassed by our parents as teenagers, it’s a revelation to want to show them off as adults. It’s also a way of saying thanks for raising us: We get you now.

But it’s not entirely selfless. There’s a level of projection, at least for me, that goes into sharing mom’s old photos. It’s a lot easier to see beauty in others than in yourself. Seeing it in your mom is a nice sturdy negotiation of the two.

It takes crossing a generation gap to appreciate those pictures. Looking at a photo of your mom taken before you were born is momentarily orphaning. It’s a record of a time when she didn’t even know you’d exist. An isolating notion as a child, it’s a revelation as an adult.

Seeing my mom free of worry, at least when it comes to my well-being, allowed me to see her as a person I might have been friends with. She liked to wear costumes, she traveled on a whim, she met random guys with hearty beards, and even once, a monkey (which she apparently took in as a pet for six months). Instead of offering the standard pert and practiced family portrait smile, she barely noticed the flash go off. There’s no gathering of family members awkwardly waiting for the snap of a shutter. In old photos, she hardly seems to have the patience to stand in one place. Her eagerness to know what will happen next is broadcast through every trip, every hairstyle, every tailor-made frock. Not only can I relate to her, I want to be her. It’s a similar feeling I get trolling Tumblr blogs of slightly younger strangers (yeah, I’ll admit) whose lives seem fuller and more thoroughly lived than my own. Only this is my mom—that is, before she was my mom.

All told, her vintage photos possess every ingredient for the perfect Facebook photo: well traveled, exotically dressed, and casually uninterested.

It’s something I’ve never been able to pull off and never will. Despite the befuddlement of many moms when it comes to the fine art of social network profiles, they seemed to know inherently how to do it better. Maybe it’s because they didn’t care about self-projection then, the way we do now. They dressed for the moment, not the moments after when they’d story-produce their adventure for online followers. Certainly, my mom never expected thousands of strangers to see her photo more than 50 years after it was taken. But she did always say, “When you have kids, your life is no longer your own.” Wise lady.

Piper Weiss, A&S ’00, is author of the book My Mom, Style Icon, to be published by Chronicle Books in May.