A young lab assistant attended an autopsy at the Johns Hopkins Hospital morgue on October 4, 1951. The assistant was Mary Kubicek. The autopsy was of a woman who had died at 31 from the metastasized cervical cancer that had so ravaged her there was scarcely an organ in her body not riddled with malignancies. Kubicek had never seen a corpse before and tried to avert her gaze from the face to the hands and feet. That’s when she was startled by the deceased woman’s chipped red toenail polish. Kubicek later told writer Rebecca Skloot, “When I saw those toenails, I nearly fainted. I thought, ‘Oh jeez, she’s a real person.’”

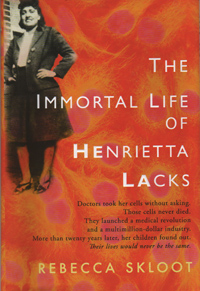

The real person was Henrietta Lacks. Much of the American public knows at least the outline of her story since publication of Skloot’s best-selling book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. When Lacks came to Hopkins for treatment of her cancer, a surgeon sliced away small samples of the malignancy and Lacks’ healthy cervical tissue for George Gey, the director of tissue culture research at Hopkins. By 1951, Gey was nearly 30 years into a quest to culture “immortal” cell lines: human cells that would reproduce endlessly in test tubes to provide a steady supply of cells for medical research. Gey had experienced little but failure when a Hopkins resident dropped off the pieces of Henrietta’s tissue. Soon after the malignant cells, labeled “HeLa,” were placed in culture medium by Kubicek, who was Gey’s lab assistant, they began to reproduce, doubling within 24 hours. They have never stopped. They now live by the uncountable trillions in laboratories and the inventories of biologics companies throughout the world, still robust after 60 years and perfect for all sorts of research. The HeLa cell line has been the foundation of a remarkable number of medical advances, including the polio vaccine, the cancer drug tamoxifen, chemotherapy, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization, and treatments for influenza, leukemia, and Parkinson’s disease.

Though the science and history in Skloot’s book are fascinating, they are not what has made it a national best seller. What has resonated with readers are the interwoven narratives of Henrietta Lacks’ sad life and her daughter Deborah’s pursuit of knowledge about the mother she never knew. And there is one more thing. Text on the front cover of Skloot’s book reads, “Doctors took her cells without asking.” The inside flap continues, “Henrietta’s family did not learn of her ‘immortality’ until more than 20 years after her death, when scientists investigating HeLa began using her husband and children in research without informed consent. And though the cells had launched a multimillion-dollar industry that sells human biological materials, her family never saw any of the profits.” A significant segment of the public harbors a deeply rooted mistrust of medical research. They do not trust physicians and scientists to be open and honest with them. They fear that the privacy of their medical records will not be respected. They believe that someone somewhere is making a lot of money off of drugs and biological products that were developed using pieces of tissue from people who now are entitled to a piece of the profits. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks speaks to that skepticism, and above all is the vivid testament of how the Lackses feel they’ve been treated by physicians, researchers, journalists, and corporations. The book will not reassure those already suspicious that they are being used. Skloot says, “The thing that I hear more than anything [from readers] is, ‘We want to know what’s going on. We don’t want to feel like someone is doing something behind our backs.’” People want their individual humanity acknowledged and respected. Physicians and scientists and ethicists know this. They also know that doing the right thing, which can seem so straightforward to the public, gets more complicated all the time.